History

Tasmania was named Tasmania, instead of Van Diemen’s Land, because of a need to push the island’s history back as far as possible beyond 1803. The Dutch explorer Abel Janszoon Tasman was usefully iconic partly because he had nothing to do with convicts. But yearning for a distant past, a past cut off from the present, was common among nineteenth-century Europeans. As John Stuart Mill remarked, ‘comparing one’s own age with former ages’ was suddenly an everyday habit. The fact that several generations divided Tasman’s visit from British settlement was almost an advantage.

... (read more)Martin Krygier’s deft, discursive prose could persuade anyone except an ironclad ideologue that it is exhilarating as well as healthy to examine one’s prejudices and complacencies. Krygier is also a writer possessed of a frank openness that gives credence to the idea that you can judge a book by its cover. I suspect he’d also enjoy the piquancy of maxim busting. The cover of Civil Passions is a particularly beautiful one: a detail of Ambrogio Lorenzetti’s 1338–40 fresco, the Allegory of Good Government. Its Giottoesque precision and its colour – those luminous Sienese pinks and reds – would be reason enough to use it. But there is a deeper fitness to the choice, and it has to do with what Krygier describes as his destined mode of being: one of hybridity.

... (read more)The Indonesian Presidency: The shift from personal toward constitutional rule by Angus McIntyre

So much has been said or written about Indonesia’s political changes since 1998 it might be thought that there was little original that could be added. Then along comes Angus McIntyre with his own particular interpretation of Indonesian politics. McIntyre has long been interested in the psychological make-up of Indonesia’s political leaders and has written some fine papers on the subject, the core of which are in his new book, The Indonesian Presidency: The Shift from Personal toward Constitutional Rule. His approach has been to examine the personalities of dominant individuals as a key explanatory factor in Indonesian politics. As a conceptual counter to Richard Robison and Vedi Hadiz’s recent book, Reorganising Power in Indonesia (2004), McIntyre’s approach similarly begs the question as to whether it is structure or agency that shapes events. In this, McIntyre almost entirely ignores structure, at least beyond the malleable Indonesian constitution.

... (read more)Seeking Racial Justice by Jack Horner & Black and White Together by Sue Taffe

The Federal Council for the Advancement of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders (FCAATSI) was a national organisation that existed, in one form or another, from 1958 to 1978. For the main part, it drew its members from a network of both black and white groups, from active citizens and from those who wanted to be counted as such.

Two recent books examine the impact and legacy of this organisation. Black and White Together, by Sue Taffe, provides a detailed overview of the organisation from an historian’s perspective, while Seeking Racial Justice is an ‘insider’s memoir’, written by one of its non-indigenous members, Jack Horner. Both books tell this story in the context of the political shift from segregation to assimilation policies (1938–61), from assimilation to integration (1959–67), and from integration to self-determination (1968–78).

... (read more)God’s Willing Workers: Women and religion in Australia by Anne O'Brien

For Germaine Greer, the nuns at the Star of the Sea Convent in Melbourne provided ‘a terrific education’. ‘They really loved us,’ said Greer. Not so Amanda Lohrey. Her experience of a working-class convent school in Tasmania so scarred her that still today, visiting a church in Europe, she feels a ‘physical revulsion’ for ‘the naked martyrs, staked out, flayed alive, crumpled, bleeding’. For former Catholic schoolgirls, a reunion is a chance to laugh together over some of the more outrageous things taught to them by nuns. But Lohrey can look back only with bitterness, in particular on the nuns’ ‘intense but evasive’ preoccupation with sex. ‘Boys are after only one thing, girls. They’ll suck you dry like an orange,’ she was told. She cannot laugh.

... (read more)In earlier works, Russian-born historian Elena Govor has written of changing Russian perceptions of Australia between 1770 and 1919 and – in My Dark Brother (2000) – of a Russian-Aboriginal family. In her latest book, Russian Anzacs in Australian History, the canvas is broader. She investigates the third largest national group (after the British and Irish) to enlist in the First AIF. Her indefatigable and imaginative research has taken her on a ‘quest for the thousand Russian Anzacs’ who comprised ‘a virtual battalion’. More exactly, they amounted to one in every four male Russians who were in Australia at the outbreak of the Great War.

... (read more)Modern Afghanistan: A history of struggle and survival by Amin Saikal

Modern Afghanistan provides a nuanced understanding of developments in a country that has attracted the attention of academics and analysts for more than two decades. A number of good books have appeared dealing with politics in and around Afghanistan since the early 1980s. Amin Saikal’s recent book benefits from these accounts, but differs in one way: it is an insider’s account, with objectivity instilled by distance and academic training. As an Australian of Afghan origin, and as an expert on the politics of West and Central Asia, he draws upon a wealth of printed, oral, political and sociological research to delve into the creation and problems of Afghanistan.

... (read more)A Shifting Shore: Locals, outsiders, and the transformation of a French fishing town, 1823-2000 by Alice Garner

Alice Garner asks us to ‘dip our toes’ into the history of the shifting shore of the Bassin d’Arcachon, but she is being coy. Her study of sea change and social conflict in the nineteenth century (for the most part) in this particular part of south-west France demands that we need to wade with her into the deep waters of exhaustive primary sources. As a research fellow in the History Department at the University of Melbourne, she is indefatigable and meticulous. This presumably well satisfies the requirements of academe, and shows her to be a fine historian, but it tends to dampen some of the liveliness that might have more easily seduced the general reader to the stories of ambition, progress, counter-attack and conflict that resulted in a resounding win for development and tourism in an age when industrialisation and railways, architectural conceits and money turned a coastal fishing and oyster-fishing area into a ‘bathing resort’.

... (read more)Frontier Justice: A History of the Gulf Country to 1900 by Tony Roberts

The country south-west of the Gulf of Carpentaria, where wild rivers tumble from stony ramparts through coastal scrub plain to the sea, was one of the last places in Australia where settlement was attempted; more integrated with Asia to the north – thanks partly to the sojourning Macassans – than Melbourne or Sydney to the south, let alone London; a world where Aboriginal society was strong enough to resist dispossession, surviving, despite everything, to this day. It has also been something of a last frontier for historians.

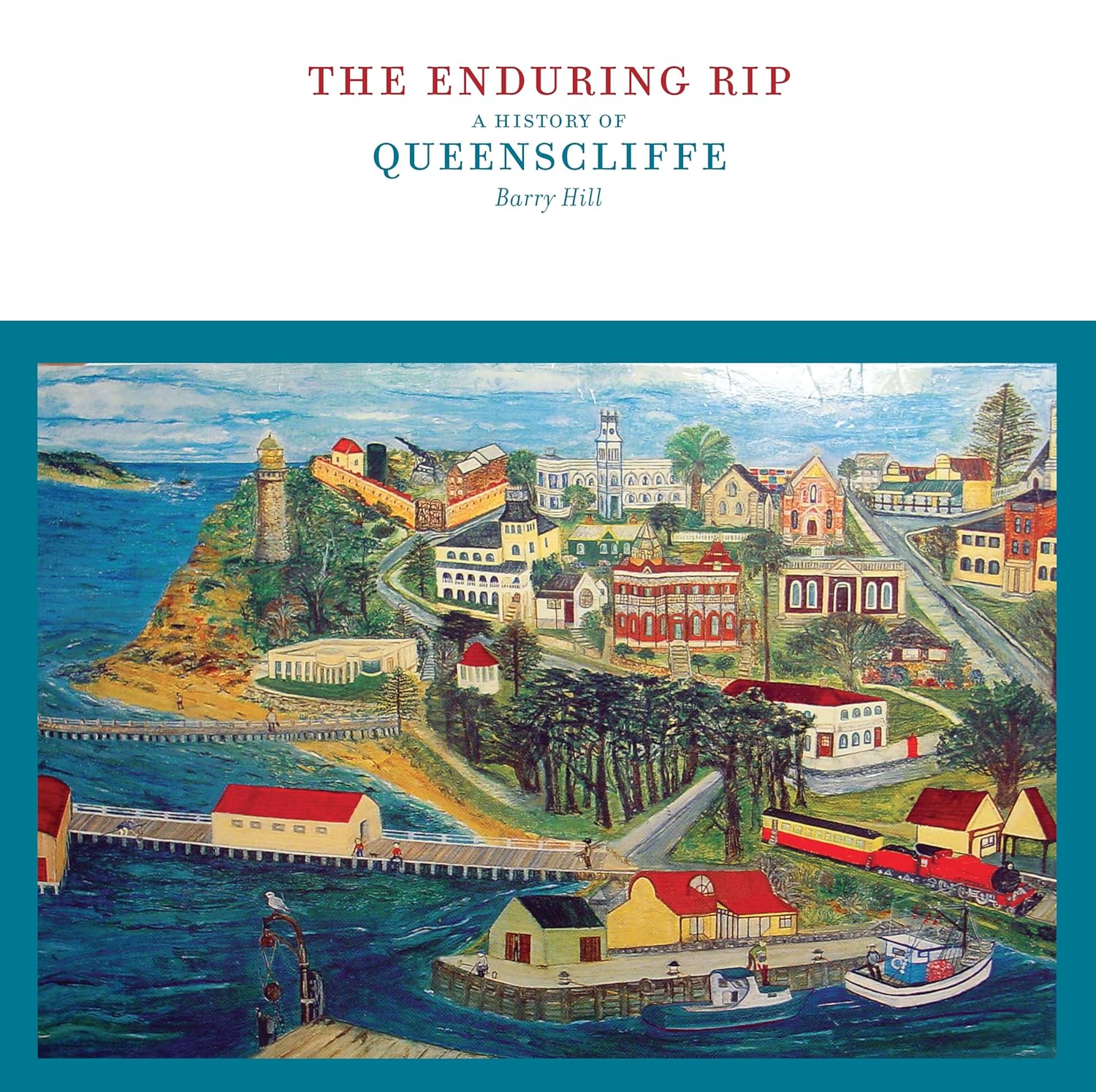

... (read more)Victoria’s coastal borough of Queenscliff is fortunate indeed to have esteemed poet and scholar Barry Hill (a local resident since 1975) as its official historian. He combines an eye for events that will resonate as part of the ‘big picture’ of Australian history with a local’s affection and instinct for the telling details that pinpoint the intrinsic character of the place.

This book was partially written in the Queenscliff Historical Museum: at a mess table recovered from a shipwreck, surrounded by vintage diving equipment, a skull recovered from the sea, music boxes and silver teapots. It is an apt metaphor for the character of the town: on one hand, a sedate seaside resort known in its heyday for its boarding houses, grand hotels and ‘solid respectability’; on the other, a notorious shipwreck site and home to both a military barracks and, more recently, an Australian Secret Intelligence Service (ASIS) training ground for spies.

... (read more)