Language

The Language Wars: A History of Proper English by Henry Hitchings

Henry Hitchings has written a number of well-received books on aspects of the English language, including Dr Johnson’s Dictionary: The Extraordinary Story of the Book That Defined the World (2005) and The Secret Life of Words: How English Became English (2008), which focuses on the numerous borrowings that English has made from other languages.

... (read more)Dictionaries of slang have a history as long as that of dictionaries of Standard English, and both kinds of dictionary arose from a similarity of needs. The need for a guide to ‘hard’ words generated the earliest standard dictionaries; the need for a guide to the language of ‘hard cases’ (beggars, thieves, and criminals generally) generated the earliest slang dictionaries. Samuel Johnson produced his Dictionary of the English Language in 1755. In 1785 Francis Grose published A Classical Dictionary of the Vulgar Tongue, a work that includes an array of slang words that would never find a home in Johnson’s lexicographic world. Similarly, when the Oxford English Dictionary project was producing its first fascicles at the end of the nineteenth century, an alternative view of what constitutes the lexicon of English was presented in A. Barrère and C.G. Leland’s A Dictionary of Slang, Jargon and Cant (two volumes, 1889–90) and in J.S. Farmer and W.E. Henley’s Slang and Its Analogues (seven volumes, 1890–1904).

... (read more)The ‘secret language’ of the title of this book covers many kinds and levels of secrecy (things hidden and concealed), and a similar range of languages. The reasons for secrecy in language are manifold, the book argues, and Barry Blake gathers into his survey a vast range of material that illustrates how people can be oblique or indirect in their uses of language, which can be characterised by the blanket term ‘secret’. While the primary focus is on English, Blake often uses examples from past languages (Latin, Greek, Old Norse), from geographically dispersed languages spoken today, and especially from the Australian Aboriginal languages that were his field of expertise when Professor of Linguistics at La Trobe University.

... (read more)Colonial Voices: A Cultural History of English in Australia 1840—1940 by Joy Damousi

This is a book about the role of English speech in the creation and spread of British colonialism in Australia, about the eventual disintegration of this imperial speech and its values in the colony now transformed into a nation, and about the emergence of the ‘colonial voices’ of the title ...

... (read more)Ernest Gowers: Plain words and forgotten deeds edited by Ann Scott

Ernest Gowers is remembered, if at all, for the writings on the English language which he undertook towards the end of his life. In 1948, at the request of the British Treasury, he wrote a small book called Plain Words. It was intended for the use of civil servants, not all of whom appreciated it, but it attracted a far wider audience, sold in huge numbers, and has never been out of print. An expanded version, entitled The Complete Plain Words, appeared in 1954. Subsequently, the Clarendon Press asked Gowers to produce a revised edition of H.W. Fowler’s Modern English Usage (1926). He laboured on the task for nine years, completing it at the age of eighty-five.

... (read more)Nothing, it seems, is too small to have its own history. As academic disciplines such as the history of ideas have grown and prospered, popular non-fiction has followed suit, offering the history of a word, a concept, a technology. This has proven to be a highly effective method of opening up the processes of culture for closer inspection, and for revealing the contingent or motivated roots of what we now take for granted. It has become an appealing and often lively way to write cultural histories.

... (read more)Speaking our Language: The story of Australian English by Bruce Moore

Sir James Murray, the famous editor of the Oxford English Dictionary, believed that the dictionary-maker’s job was to furnish each word with a biography.

... (read more)Worrying About China: The language of Chinese critical inquiry by Gloria Davies

Gloria Davies quotes William Blake in the acknowledgments to her book: ‘true friendship is argument.’ When choosing that quote, I wonder if she had the Chinese concept of zhengyou in mind. That is the word Kevin Rudd chose for friendship when he spoke to the students at Peking University in April this year. Zhengyou is not just about friendship, for which there is another Chinese word (youyi); it defines a true friend as one who dares to disagree.

... (read more)Translating Lives: Living with two languages and cultures edited by Mary Besemeres and Anna Wierzbicka

Language shapes identity: everyone knows that, in theory. Anyone who has studied a foreign language knows that exact equivalents do not exist for every word. Translation cannot be perfect: something is always lost. So what happens when people, used to one linguistic identity, have to translate themselves into a new language? Mary Besemeres and Anna Wierzbicka have assembled twelve witnesses to give personal accounts. All are academics or writers who possess the intellectual resources to make sense of what they have encountered, while at the same time registering the dislocations they have experienced. All write English fluently: they are not concerned with the difficulties of learning English but of being themselves in Australian English. Some make the comment that they are perfectly comfortable writing academic English while still finding the small transactions of daily life a challenge.

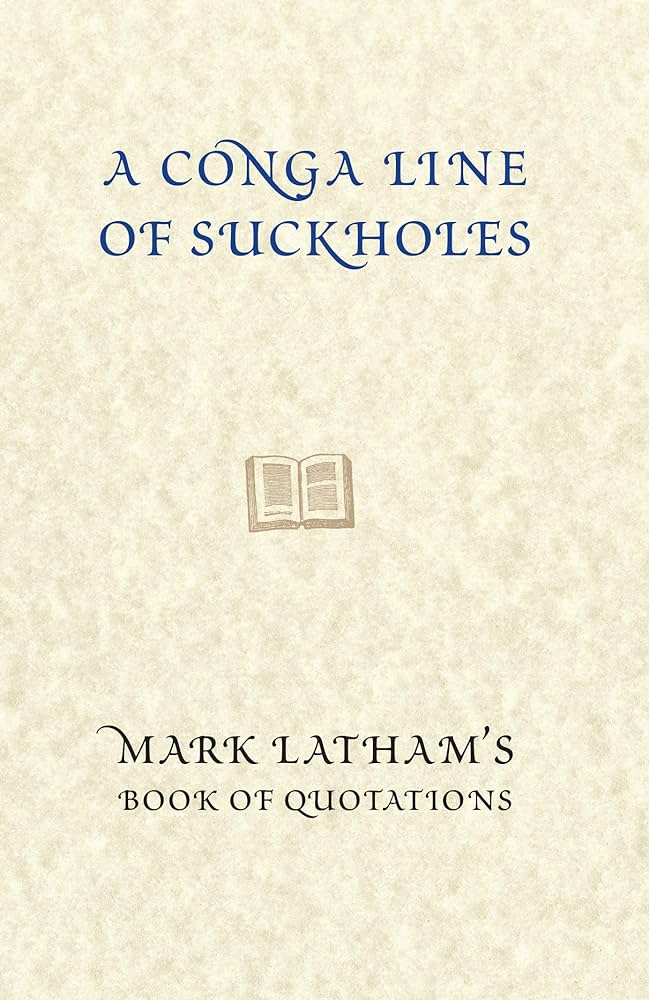

... (read more)A Conga Line of Suckholes: Mark Latham’s book of quotations by Mark Latham

This is a selection of the quotations Mark Latham collected during his time in local and federal politics. The quotations are arranged alphabetically by subject, from ‘Aboriginal People’ to ‘Working Class’. Given Latham’s career, it is not surprising that the emphasis is on political quotations and quotations from politicians.

Some quotations are quite familiar, as with Winston Churchill’s comment on a former Conservative MP who was seeking to stand as a liberal: ‘The only instance of a rat swimming towards a sinking ship.’ I was touched by Archbishop Desmond Tutu’s incisive critique of colonising missionaries: ‘When the missionaries first came to Africa they had the Bible and we had the land. They said “Let us pray” and when we opened our eyes, we had the Bible and they had the land.’ Charles de Gaulle demonstrates Gallic culinary wit: ‘How can you govern a country which has 246 varieties of cheese?’ Readers will find their own favourites.

... (read more)