Language

Diggerspeak: The language of Australians at war by Amanda Laugesen

by Gary Simes •

Australia's Language Potential by Michael Clyne

by Bruce Moore •

A Word On Words by Pam Peters & Away With Words by Ruth Wajnryb

by Fred Ludowyk •

Death Sentence: The decay of public language by Don Watson

by Julian Burnside •

The Uncyclopedia by Gideon Haigh & Names From Here and Far by William T. S. Noble

by Fred Ludowyk •

The Cambridge Encyclopedia Of The English Language (Second Edition) by David Crystal

by Bruce Moore •

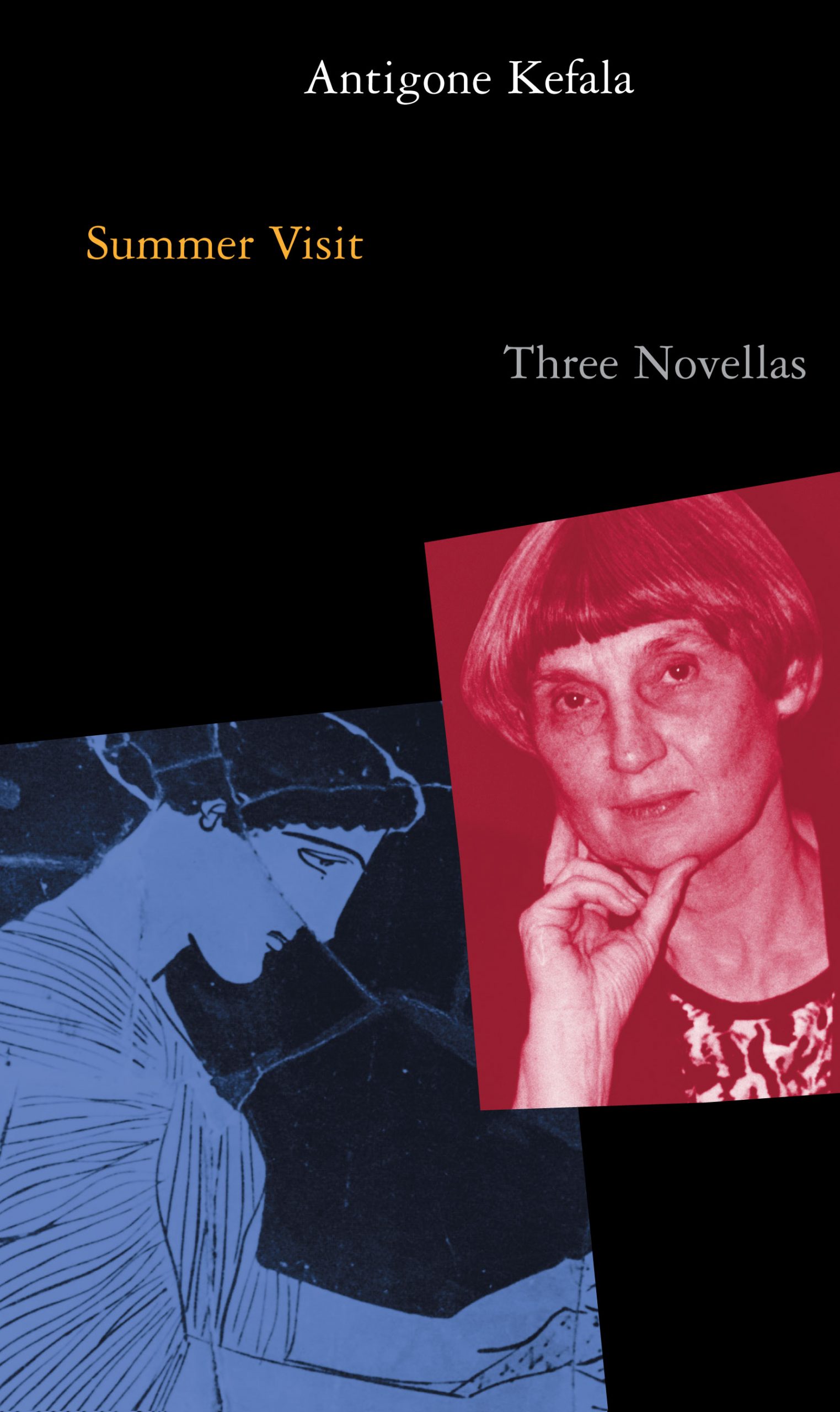

Summer Visit by Antigone Kefala & The Island/L’île/To Nisi by Antigone Kefala

by Stathis Gauntlett •