Literary Studies

How would we have viewed the seven hundredth anniversary of Dante Alighieri’s death if there had been no Covid-19? The editors of Divining Dante are candid about their fears that the pandemic might narrow their celebratory anthology to poems of doom and disaster. After all, the cosmic system of Dante’s Comedy is one of the few fictional creations to match the scale and reach of the pandemic. Dante’s souls are aware of their insignificance among millions, but their pain or bliss is unique and absolutely meaningful. Punishments or blessings are matched to their deeds; character is fate. Today we, too, are confined to private places and must face whatever we find there. The times suit that side of Dante.

... (read more)No contemporary Australian writer has higher claims to immortality than Gerald Murnane and none exhibits narrower tonal range. It’s a long time since we encountered the boy with his marbles and his liturgical colours in some Bendigo of the mind’s dreaming in Tamarisk Row (1974). There was the girl who was the embodiment of dreaming in A Lifetime on Clouds (1976). After The Plains (1982) came the high, classic Murnane with his endless talk of landscapes and women and grasslands, like a private language of longing and sorrow and contemplation.

... (read more)Continent of Mystery: A Thematic History of Australian Crime Fiction by Stephen Knight

Continent of Mystery, subtitled ‘A thematic history of Australian crime fiction’ is, in the most simplistic terms, a daunting and inspiring book. My Australian crime fiction, mystery and detective fiction magazine, Mean Streets, was launched by Knight towards the end of 1990, not long before his move to the United Kingdom. For better or worse upon Knight’s departure I assumed, or at least so I was told, the mantle of Australia’s expert on crime fiction. I always perceived that observation as a compliment but having read Continent of Mystery with a sense of awe I can only say that I’m not sure I’m even fit to sit at Knight’s feet when it comes to local fiction with criminality at its core.

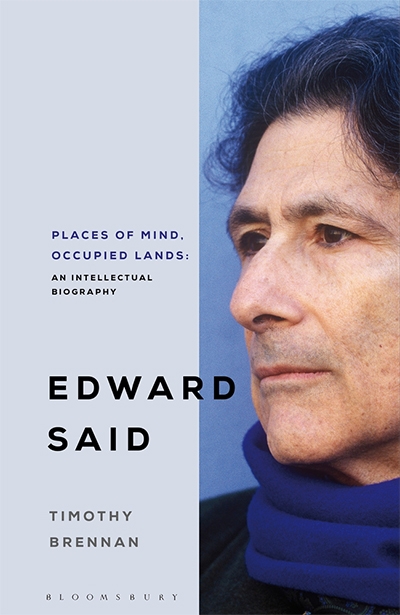

... (read more)When the leukaemia with which he had been diagnosed in 1991 claimed his life twelve years later, Edward W. Said left behind more than the usual testaments to a successful academic career: landmark studies, bountiful citations, bereft colleagues, and the cadres of pupils whose intellectual maturation he had overseen. More importantly, he embodied a many-sided ideal of intellectual and civic engagement that combined the vita contemplativa with the vita activa. A professor in Columbia University’s Department of English and Comparative Literature for forty years, Said was a member of the exiled Palestinian National Council and arguably the most visible advocate for the Palestinian cause throughout his later life.

... (read more)In my thirty years as an academic, the greatest joy and puzzlement I had was in teaching poetry. I agree with T.S. Eliot that ‘genuine poetry can communicate before it is understood’. Our best teaching often involves what we do not fully understand. The scholar D.S. Carne-Ross once argued that, upon hearing poetry spoken in an unfamiliar language, you can tell it is poetry, the language of poetry, which is other than what I do in writing this review. Anyone faced with the problem of teaching poetry in an academic setting will realise that part of the problem is the academic setting itself. Poetry has thrived for millennia everywhere on earth without the benefit of professors, classrooms, and theories of reading. How, then, might we teach it?

... (read more)The Seasons: Philosophical, literary, and environmental perspectives edited by Luke Fischer and David Macauley

There is something quaint about seasons. They do not seem to trigger the same dread that we now experience when we hear the word ‘climate’. I think this is because seasons remain connected to that time in human history during which the annual variations of climatic conditions were evidence of an underlying stability in the world and of nature’s constancy. The Seasons, a collection of essays edited by Luke Fischer and David Macauley, is an attempt to think through the ongoing role that seasons have within human imaginaries. Both editors are philosophers and the book is mainly grounded in forms of analytic philosophy insofar as seasons (and seasonality) are posited as concepts susceptible to abstract contemplation. The approach is inflected by a certain eclecticism of thought and example, but there is also an underlying intellectual and tonal consistency. The prominence of Goethe, Hölderlin, Keats, and Thoreau within the book, for instance, firmly roots the contributions within the romantic imagination. Other key reference points in the book – Rilke, Heidegger, Merleau-Ponty, Rachel Carson – remain within the long shadow of European romanticism.

... (read more)Fishing for Lightning: The spark of poetry by Sarah Holland-Batt

Sarah Holland-Batt’s Fishing for Lightning is a book about Australian poetry. As such, it is a rare, and welcome, bird in the literary ecology of our country. It is welcome because poetry, like any other art form, requires a supportive culture that educates and promulgates. Not that Holland-Batt, herself one of our leading poets, is ‘merely’ didactic, or a shill for the muses. Holland-Batt, who is also an academic, writes with great authority and insight, and she is a fine stylist, penning essays that are packed with humour and playfulness. These essays cater for all kinds of audiences, from newcomers to poetry experts, which is no small feat.

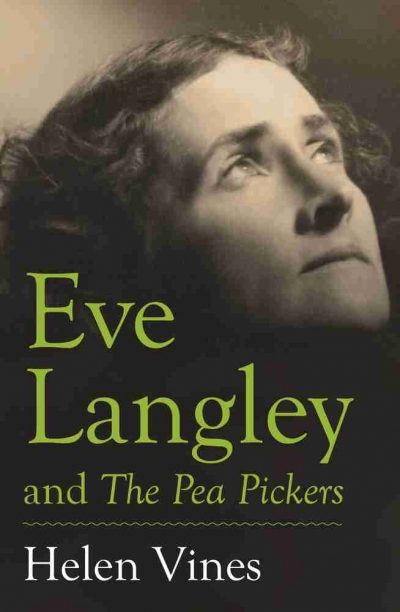

... (read more)In 1942, The Pea Pickers was published by Angus & Robertson in Sydney, garnering high praise for its freshness and poetic invention. A picaresque tale of two sisters who, dressed as boys, earn their living picking seasonal crops in Gippsland in the late 1920s, it impressed Douglas Stewart, literary editor of the Bulletin, with its ‘love of Australian earth and Australian people and skill in painting them’. The author, Eve Langley, was at that time incarcerated in the Auckland Mental Hospital, where she would remain for the next seven years, isolated from her estranged husband and three young children, and from her mother and sister, who were also in New Zealand.

... (read more)Walter Scott at 250: Looking forward by Caroline McCracken-Flesher and Matthew Wickman

Walter Scott, born on 15 August 1771, turns 250 in 2021. This event has been celebrated in Scotland with events such as a ScottFest at ‘Abbotsford’, his home, and a major international conference. But Scott, almost certainly the most popular and widely known author in the world in the nineteenth century, fell disastrously in public and critical esteem, to the point that E.M. Forster, in his influential Aspects of the Novel (1927), could sum him up with the wearily dismissive question ‘Who shall tell us a story?’ and the equally dismissive answer ‘Sir Walter Scott of course’. For Forster, Scott had ‘a trivial mind and a heavy style’.

... (read more)The Oxford Handbook of Dante by Manuele Gragnolati, Elena Lombardi, and Francesca Southerden

With its finely honed critical readings and ‘transversal connections’, The Oxford Handbook of Dante is a timely and masterful collection of forty-four chapters presenting contemporary critical insights from a broad choice of intellectual fields that range from Italian and European perspectives to Anglo-American approaches. Highlighting Dante’s expansive outreach over the centuries, the editors, Manuele Gragnolati, Elena Lombardi, and Francesca Southerden, have assembled an impressive array of scholarly voices whose contributions offer a robust critical collection not exclusively intended for specialist readers.

... (read more)