Media

The Content Makers: Understanding the media in Australia by Margaret Simons

Margaret Simons is a writer familiar to her readers. There she was in Fit to Print: Inside the Canberra press gallery (1999), first driving with her husband and young children to the national capital, then following Michelle Grattan’s blue dress around Parliament House. Here she is again in The Content Makers: Understanding the media in Australia, telling us about her experiences in daily journalism, her move into freelance journalism, writing for the e-mail news service Crikey, and attending last year’s infamous 2006 Walkley Awards dinner.

... (read more)Identity Anecdotes: Translation and media culture by Meaghan Morris

In October 2006, the Australian Literary Review published a list of the forty most influential Australian intellectuals, the results of a peer survey undertaken by the Australian Public Intellectual Network. Meaghan Morris ranked seventh, sharing her berth with Tim Costello and Inga Clendinnen. Leaving aside the problems, exclusions, and biases that attend the compilation of such lists, I was heartened to see Morris’s name in the top ten. Theory and cultural studies have long been demonised outside the academy, and their position within the university system remains subject to sniping. As a writer, critic and editor, Morris’s work over the last two decades has defined Australian cultural studies – indeed, she co-edited Australian Cultural Studies (1993) – and the results of this survey suggest at the very least a reluctant recognition of her contribution to Australian intellectual life. Identity Anecdotes: Translation and Media Culture is neither a defence of cultural studies nor an overview of Morris’s prodigious career. Rather, it is an eclectic collection of essays, written between 1998 and 1999, which are all more or less obliquely concerned with questions of Australian culture and history. It offers a virtuosic demonstration of the capacities of theoretically informed cultural and historical criticism.

... (read more)1980: a red-haired girl in my Year Ten art class at John Gardiner High School asked me if I knew there was a radio station that only played ‘that new wave music’. She said it with a measure of contempt in her voice – for me and for it. But I was tempted, and soon became part of 3RRR’s small, staunch audience. A quarter of a century on comes Mark Phillips’s lively, if listy (though no more than Ken Inglis’s ABC histories) narrative of this Melbourne institution’s first thirty years.

... (read more)Narrative and Media provides a lengthy and extensively researched overview of one of the central features of contemporary popular culture. The four authors (all of whom have been scholars at Sydney University) discuss the roles that narrative has played in mediums such as television, cinema and radio. In the introductory chapter, the authors explain the importance of their topic: ‘In a world dominated by print and electronic media, our sense of reality is increasingly structured by narrative.’ Later chapters address issues such as ‘narrative time’, ‘print news as narrative’, and the impact upon narrative conventions of postmodern and post-structuralist thought. In doing this, the authors also provide a ‘consideration of industry-related issues that affect the production and consumption of media texts’.

... (read more)Fremantle’s first real newspaper, The Herald, saw the light of day in a building on the corner of Cliff and High Streets on Saturday, 2 February 1867. The brainchild of two ex-convicts, James Pearce and William Beresford, it soon became the main voice of opposition to colonial autocracy, as well as the voice of Fremantle itself.

... (read more)Switched On: Conversations with influential women in the Australian media by Catherine Hanger

Switched On showcases the careers of twenty-nine ‘influential’ women who work in the media. Catherine Hanger, interviewer and former editor of Vogue Australia, believes that Switched On ‘connects two major spheres of influence in our society – the media and the women who work in it’ – and argues that the influence of these women is ‘very powerful indeed’. While the title promises ‘conversations’, Hanger, strangely, omits her questions. Perhaps she asked just one: ‘How did you become editor of Australian Women’s Weekly/an SBS news presenter/a film reviewer/a PR adviser to PBL/host of Media Watch?’

... (read more)Australian historians admire Robert Menzies. Pardon? Aren’t historians, like the rest of the Australian academy, left-wing propagandists? Don’t they all loathe the prime minister’s political role model? Regardless of how historians view Menzies’ attitudes to the monarchy, appeasement, the middle class and the Communist Party, they have reached a consensus on one point: Menzies played a significant role in the consolidation and expansion of Australia’s university sector. When Ben Chifley laid the foundation stone of the Australian National University during the election year of 1949, Menzies refused to politicise the initiative; as prime minister in 1956, he appointed a committee to inquire into the plight of Australian universities and insisted on the provision of life-giving funds by the Commonwealth government under conditions which preserved university autonomy. As his biographer, A.W. Martin, notes, ‘Menzies’ support of universities, and the university life, was never at any time in doubt’.

... (read more)The Sydney Morning Herald has been ‘Celebrating 175 Years’ all year. The words adorn every front page; the Herald ran a number of commemorative features to mark the actual anniversary on April 18; and The Big Picture: Diary of a Nation, consisting of essays by journalists and photographs from the Herald’s magnificent photographic library, has been published (see John Thompson’s review in the March issue).

... (read more)An Indian fast-food outlet has named itself after Mahatma Gandhi and features a caricature of his face in neon lights. Tacky? Certainly. Only in America? Only in Australia, actually, or at least that’s what a major cable television channel would like to suggest.

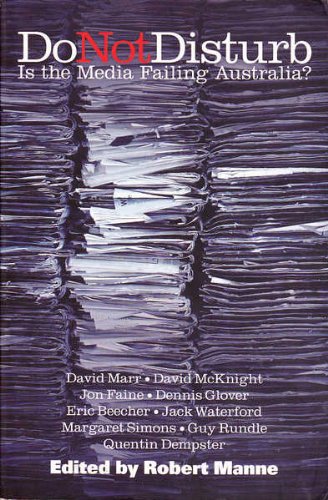

... (read more)Do Not Disturb: Is the media failing Australia? edited by Robert Manne

Rupert Murdoch is the Napoleon of our times. He has gone on conquering largely because certain governments – Bob Hawke’s among them, in early 1987 – have persistently acquiesced, changing or moderating regulations as his battle plans required. It was once possible to view him as bound, in George Munster’s phrases, ‘on a random walk … [on which] despite the ever greater accumulation of means in his hands, he contributed more and more to the spreading confusion about ends’. That was written more than twenty years ago; Munster’s great book, A Paper Prince (1985), remains valid as a rigorous and witty account of Murdoch’s rise, and as an exemplary study of the relations of media, money and politics. But that walk is not so random now.

... (read more)