Politics

God Save the Queen: The strange persistence of monarchies by Dennis Altman

Dennis Altman recently published a slice of autobiography, Unrequited Love: Diary of an accidental activist, addressing ‘his long obsession with the United States’. Now, as if to remind us that his training has been in political science, Altman presents us with this lively survey of monarchies old and new, constitutional and absolute, European and Asian. It has its origins in the Economist democracy index, according to which seven of the ten most democratic nations were constitutional monarchies. The list is dominated by the Scandinavian kingdoms, with Norway at the top, and former dominions of the British Empire, with Australia just scraping into the list at equal ninth with the Netherlands. As a committed republican, Altman was set thinking by this apparent alliance of monarchy and democracy.

... (read more)JFK: Coming of age in the American century, 1917–1956 by Fredrik Logevall

Writing this review of John F. Kennedy’s formative years soon after the end of the Trump regime has evoked some surprising parallels between these two one-term American presidents (and perennial womanisers). They were both second sons born into wealthy families dominated by powerful patriarchs. Against the odds, they emerged as their fathers’ favourites and were groomed for success. Thanks not just to their wealth but to their televisual celebrity and telegenic families, they managed to eke out close election victories at a time when just enough disenchanted voters were looking for a change of direction in the White House. Despite their administrations’ profound disparities in competence and their differences in political outlook, they shared a deep distrust of senior bureaucrats and military officials, as well as an inability to work effectively with Congress. Bullets and ballots, respectively, ended Kennedy’s and Donald Trump’s presidencies, but not the cults of personality they had inspired. In the space of just over half a century, they have tilted the trajectory of American democracy and diplomacy from the tragic to the tragicomic.

... (read more)To Kill a Democracy: India’s passage to despotism by Debasish Roy Chowdhury and John Keane

In a recent interview, India’s foreign minister, Subrahmanyam Jaishankar, was asked whether his country was heading in what his interlocutor, the Lowy Institute’s Michael Fullilove, called ‘an illiberal direction’. Bristling, Jaishankar denied the charge. India is undergoing something quite different, he argued. It is experiencing a ‘very deep democratization’. This process might be hard for outsiders to understand, but it was positive, not problematic. After decades of rule by an English-speaking, Western-educated élite, the country was at last being governed by politicians who spoke and thought and behaved like ordinary Indians.

... (read more)The Age of Acrimony: How Americans fought to fix their democracy, 1865–1915 by Jon Grinspan

William Darrah Kelley – a Republican congressman from Philadelphia – stood at the front of a stage in Mobile, Alabama, watching as a group of men pushed and shoved their way through the audience towards him. It was May 1867, Radical Reconstruction was underway, and Southern cities like Mobile were just beginning a revolutionary expansion and contraction of racial equality and democracy. The Reconstruction Acts, passed by Congress that year, granted formerly enslaved men the right to vote and to run for office in the former Confederate states. Northern Republicans streamed into cities across the South in 1867, speaking to both Black and white, to the inspired and hostile – registering Black voters and strengthening the already strong links between African Americans and the party.

... (read more)One of the disconcerting aspects of this pandemic is that there was no shortage of warnings. For decades, virologists foresaw the coincidence of urbanisation, human proximity with animals, climate change, and globalisation as ideal conditions for spreading deadly pathogens. Science journalists wrote books with titles such as The Coming Plague (Laurie Garrett) and Spillover (David Quammen), whose conclusions were amplified by TED-talking billionaires. SARS, MERS, Ebola, and swine flu were further clues. Yet come January 2020, authorities worldwide were slow, indecisive, and ill-prepared.

... (read more)A Narrative of Denial: Australia and the Indonesian violation of East Timor by Peter Job

Peter Job, a former East Timor activist, has written a careful, dispassionate account of the stance of Gough Whitlam’s and Malcolm Fraser’s successive governments in relation to Portuguese East Timor. He has consulted a commendably wide range of oral and written sources, interviewing, for example, several retired senior Australian officials formerly engaged in the design and implementation of Timor policy. His story ends in 1983, with Bob Hawke’s election to office. Job should be encouraged to complete his account in the future to acquaint readers with developments up to at least the UN intervention in 1999 that gave Australian diplomacy a new role.

... (read more)Leadership by Don Russell & A Decade of Drift by Martin Parkinson

In 1958, the Australian political scientist A.F. Davies (1924–87) published Australian Democracy: An introduction to the political system, one of the first postwar attempts to combine institutional description with comment on the patterns of political culture. It introduced a provocative assertion: Australians have ‘a characteristic talent for bureaucracy’. Disdaining the myth of Australians as shaped by the initiative and improvisation of our bush heritage (Russel Ward’s The Australian Legend was published in the same year), Davies argued:

... (read more)The Brilliant Boy: Doc Evatt and the great Australian dissent by Gideon Haigh

To write of Herbert Vere Evatt (1894–1965) is to venture into a land where opinions are rarely held tentatively. While many aspects of his career have been controversial, his actions during the famous Split of 1955 arouse the most passionate criticism. Evatt is attacked, not only on the political right but frequently from within the Labor Party itself, for his alleged role in causing the catastrophic rupture that kept Labor out of office until 1972.

... (read more)Following 200 pages of at times harrowing detail in which former Labor MP Kate Ellis outlines the extent of the sexist and misogynist behaviour she endured as a member of the Australian Parliament, she asks herself: ‘Is it worth the hard days, the unnecessary crap?’ ‘Yes’, she replies. ‘Every. Single. Second. No question.’

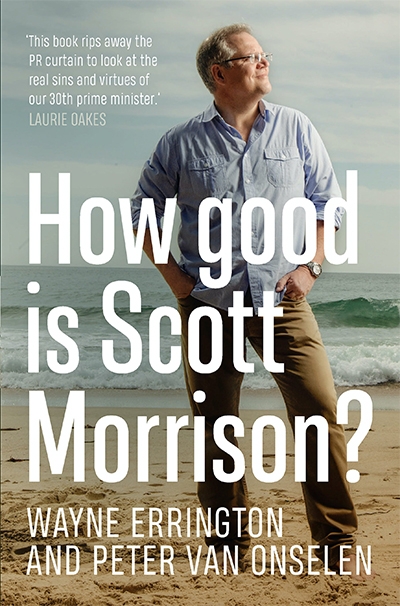

... (read more)How Good Is Scott Morrison? by Wayne Errington and Peter van Onselen

Flash back to that election night in May 2019, when Australians, depending on their party affiliation, were either overjoyed or appalled at the Coalition’s return despite the opinion polls. That evening, Scott Morrison – a man little known to Australians until assuming the prime ministership just nine months before after an ugly leadership coup – summed up Coalition sentiment and his own Christian faith: ‘I have always believed in miracles,’ Morrison said, before asking, rhetorically, ‘How good is Australia?’

... (read more)