Chinese Brecht

I was asked to interview the Chinese theatre director Meng Jinghui recently. He’s a cult figure in China, an associate director of the Beijing-based National Theatre and has over two million followers on Sina Weibo, the Chinese equivalent of Twitter.

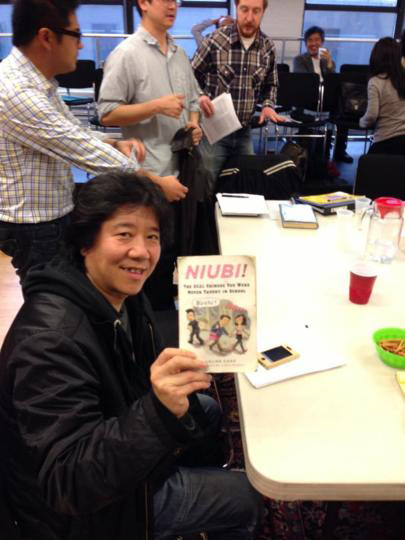

Meng Jingui holding a copy of Niubi!:The Real Chinese You Were Never Taught in School by Eveline Chao (photograph by Nick Frisch, 2013) http://evelinechao.com/Meng is known for taking things to the edge; for having, according to American academic Claire Conceison, a ‘badass’ attitude. In a recent article in the spring edition of The Drama Review, Conceison reveals that Meng’s favourite phrase is niubi, which in Mandarin means cow’s vagina. Cow’s Vagina could also describe his aesthetic, she says, slightly enigmatically, and Meng will bring it to Melbourne in June when he directs a version of Bertolt Brecht’s The Good Person of Szechuan (1943).

Meng Jingui holding a copy of Niubi!:The Real Chinese You Were Never Taught in School by Eveline Chao (photograph by Nick Frisch, 2013) http://evelinechao.com/Meng is known for taking things to the edge; for having, according to American academic Claire Conceison, a ‘badass’ attitude. In a recent article in the spring edition of The Drama Review, Conceison reveals that Meng’s favourite phrase is niubi, which in Mandarin means cow’s vagina. Cow’s Vagina could also describe his aesthetic, she says, slightly enigmatically, and Meng will bring it to Melbourne in June when he directs a version of Bertolt Brecht’s The Good Person of Szechuan (1943).

My Mandarin is non-existent, Meng’s English is rudimentary (rehearsals will be interesting), and we had half an hour. My questions were possibly convoluted, though Meng would often laugh, which I found encouraging (the humour of creative recognition perhaps?) until I received the dry little cough of an answer. It was as if the traffic of words had been conveyed in a leaky sieve or while a very noisy truck was thundering past.

The only English word he used was bullshit (should I adopt niubi as a cultural compliment? It has a certain ring). But he is a charismatic presence, with long scruffy hair, black scruffy clothes, and a disconcerting way of staring intently at you even when you are looking elsewhere; this was often the case as I willed the interpreter to match her terse scats of English to the expressive torrents of Mandarin.

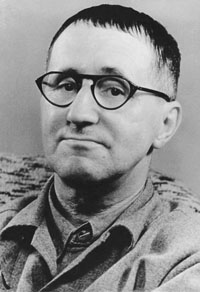

Bertolt Brecht in 1954No, Brecht’s not done much in China these days, he said, he’s rather old hat. No, continued Meng, he is not really interested in Brecht’s theories of traditional Chinese theatre and Verfremdungseffekt (alienation effect). No, it wasn’t going to be set in an imaginary China, as was Brecht’s play. Yes, materialism is rampant and young people in China today are far more individualistic. And finally, the message of the play is that money is not important but that the future is.

Bertolt Brecht in 1954No, Brecht’s not done much in China these days, he said, he’s rather old hat. No, continued Meng, he is not really interested in Brecht’s theories of traditional Chinese theatre and Verfremdungseffekt (alienation effect). No, it wasn’t going to be set in an imaginary China, as was Brecht’s play. Yes, materialism is rampant and young people in China today are far more individualistic. And finally, the message of the play is that money is not important but that the future is.

Brecht’s play, about the difficulties of being good in a corrupt and unequal society has a greater pertinence in today’s trade- and progress-obsessed China than in the world of Mao’s idealised worker, and it will be interesting to see what the local critics write when it tours there later this year. The play’s alienation effect on Australia’s wealthy and possibly complacent audiences may well have more to do with niubi aesthetics than penetrating questions about the history and economic reality of capitalist greed.

The Malthouse Theatre’s idea of inviting a renowned director from the world’s last great communist power to interpret a work set in China by one of the great Western playwrights and ideologues of the twentieth century is a form of cultural Chinese whispers. Brecht’s theatre combines Marxist ideas of alienation (of labour, through class stratification) with the aforementioned Verfremdungseffekt in Chinese acting; there is no fourth wall with the actors acknowledging the audience and commenting on the action; there are encoded gestures and acrobatics, all adding to Brecht’s aim of ‘making strange’.

Meng Jinghui (photograph by Pia Johnson) http://www.piajohnson.com/Brecht didn’t want the audience to identify with the characters on stage, but rather to ponder the historical and social realities of the times. Thickening this sense of unreality was also behind the exotic locations of his plays. The Good Person of Szechuan was written in 1943 in Finland, while Brecht awaited safe passage to America. His Szechuan was as imaginary as his Rise and Fall of the City of Mahagonny (1930) in its wasteland wilderness, or the Soho of his Threepenny Opera (1928).

Meng Jinghui (photograph by Pia Johnson) http://www.piajohnson.com/Brecht didn’t want the audience to identify with the characters on stage, but rather to ponder the historical and social realities of the times. Thickening this sense of unreality was also behind the exotic locations of his plays. The Good Person of Szechuan was written in 1943 in Finland, while Brecht awaited safe passage to America. His Szechuan was as imaginary as his Rise and Fall of the City of Mahagonny (1930) in its wasteland wilderness, or the Soho of his Threepenny Opera (1928).

As a young theatre student in 1989, Meng witnessed the clashes between army and students in and around Tiananmen Square, which led to the June 4 massacre. He has spent the past twenty-five years negotiating a changing reality of increased personal freedom and huge economic growth, travelling the world as an independent theatre maker. He was last here in 2011 with Rhinoceros in Love, written by his wife Liao Yimei. His knowledge and aesthetic is a mash of the Western canon (he did his university dissertation on the great Soviet era theatre-maker Vsevolod Meyerhold) with traditional Chinese stage traditions, mainly opera and all the cultural bricolage in between.

For Meng, Brecht’s Szechuan is an absurd cartoon; his idea of making strange may well incorporate ideas of the West as filtered through Asian eyes. I tried to winkle this out of him, but he wasn’t saying, or maybe it got lost in translation. Or maybe, like a good theatre maker, he’ll show rather than tell. We’ll have to wait and see.

The Good Person of Szechuan, Meng Jinghui’s adaptation of Bertolt Brecht’s realist parable, will be presented by the Malthouse Theatre at the Merlyn Theatre from 27 June to 20 July.

Leave a comment

If you are an ABR subscriber, you will need to sign in to post a comment.

If you have forgotten your sign in details, or if you receive an error message when trying to submit your comment, please email your comment (and the name of the article to which it relates) to ABR Comments. We will review your comment and, subject to approval, we will post it under your name.

Please note that all comments must be approved by ABR and comply with our Terms & Conditions.