William Shakespeare

Back in 1991, Bell Shakespeare opened their very first season with Hamlet, starring John Polson and directed by John Bell himself; it deliberately highlighted the Australian vernacular, almost over-emphasising the flat vowel sounds and local cadences over the fruitier delivery we inherited from the British. It had a gritty contemporary setting, and garishly over-the-top costumes. It also wasn’t very good.

... (read more)The basic facts of William Shakespeare’s life – his baptism, early marriage, three children, shareholder status in his playing company, acquisition of a coat of arms, purchase of New Place in Stratford, and his death in 1616 – are well known. Is there anything new to say?

... (read more)Holding a Mirror up to Nature: Shame, guilt, and violence in Shakespeare by James Gilligan and David A.J. Richards

Familiarity may have inured us to Shakespeare’s violence. Poison, suffocation, suicide, rape, and assassination are among the central events of his major plays. But the upper-middle-class respectability of too many Shakespeare performances and the insipid, managerial culture of academic ‘Shakespeare studies’ threaten to reduce the greatest of all dramatists to something antiseptic and safe.

... (read more)Devotees of Giuseppe Verdi often suggest that the composer’s version of Shakespeare’s Othello is ‘greater’ than the original; a fruitless assertion, but indicative of the esteem in which Verdi’s penultimate opera is held. After Aida (1871), Verdi was enjoying the life of a gentleman farmer. Italian opera of the 1870s and 1880s, however, was facing something of a crisis, threatened by the relentless tide of ‘Wagnerism’, whose theories on opera were embraced by many Italians. Verdi, when asked about his own theory of theatre, drily replied: ‘My theory is that the theatre should be full’.

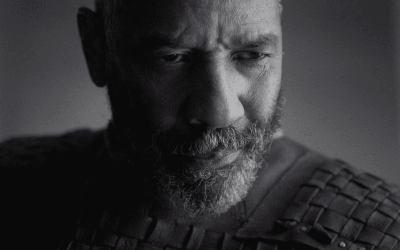

... (read more)Could Macbeth be Shakespeare’s most innately cinematic play? Even in its brief stage directions and off-stage action, it conjures up daring battlefields, horrible massacres, spine-tingling witchcraft, wandering spirits, duels on castle ramparts, and a moveable forest. Every few years another filmmaker tries their hand at it, Orson Welles (Macbeth, 1948), Akira Kurosawa (Throne of Blood, 1957), and Roman Polanski (Macbeth, 1971) notable among them. 2006 gave us Geoffrey Wright’s best-forgotten Dunsinane-does-Underbelly version, while Justin Kurzel (director of Snowtown and the recent Nitram) injected his terrific 2015 version with rousing battle sequences and a blockbuster-ready, musclebound Thane of Glamis. Now, not long after Kurzel’s film, comes The Tragedy of Macbeth from Joel Coen, working without his brother Ethan for the first time in decades. Where Kurzel’s version aimed for historical realism and cinematic virtuosity, Coen’s adaptation is faithful above all else to Macbeth’s original medium: the theatre.

... (read more)As is often the case with Shakespeare, theories and counter-theories about the provenance of As You Like It (probably 1599 or early 1600) have floated around for centuries. One such theory posits that the play is Love’s Labour’s Won, the ‘lost’ sequel – or more accurately second part of a literary diptych – to Love’s Labour’s Lost (1595–96) and that As You Like It is actually the play’s subtitle. This would align with Shakespeare’s finest comedy, Twelfth Night, which has the subtitle What You Will. Take that as you like it and make of it what you will.

... (read more)A solid wooden desk at centre stage is bracketed by two more placed behind it. A whiteboard is off to one side, and a pile of broken office chairs rises on a tiered platform, suggesting a throne. The rollers from five swivel chairs hang threateningly over the actors’ heads. As the audience is seated, actors in dour business suits enter and exit, checking papers with a sense of subdued activity as the ethereal strings, pads, and pizzicato melodies of Ben Keene’s sound design float through the space. Someone Blu-Tacks a pie chart split into three on the whiteboard, foreshadowing the play’s famous conceit. These pre-show touches promise an anachronistic corporate world with overtones of Terry Gilliam’s Brazil and the Time Variance Authority from Marvel’s recent Loki.

... (read more)Shakespeare and East Asia is one of the latest titles released in the Oxford Shakespeare Topics series. Edited by Stanley Wells and Peter Holland, the Oxford University Press series is pitched at the elusive general reader who is seeking a primer on one of the many topics proliferating within the bustling industry of Shakespeare studies. Written by one of the directors of the MIT Global Shakespeares Archive, this book invites readers to think about the significance of Shakespeare’s continuing influence on cultural production in the Far East, and how Asian adaptations of his corpus participate in creating a contested image of Asia for audiences both in the region and in the Anglophone West. Assembling a varied body of cinematic and theatrical reworkings of Shakespeare from countries like Japan, Korea, China, Taiwan, Hong Kong, and Singapore, Joubin tells a story about Asian Shakespeares that is also a story about how a particular region has negotiated the imperatives of globalisation and the tacit anglicising effects of global culture.

... (read more)As the third Verdi opera on offer in Melbourne this season (along with Opera Australia’s Aida and Ernani), Melbourne Opera’s production of Verdi’s Macbeth at Her Majesty’s Theatre is a mixed offering. Verdi wrote Macbeth – one of his earliest operas and less celebrated than his later Shakespearean works, Otello (1887) and Falstaff (1893) – when he was thirty-three; it had its première in Florence in 1847. Both musically and dramatically, it is clearly rooted in the bel canto era, which prioritised beautiful singing above all else. In 1865, Verdi revised the opera for the Paris Opera. Usually, one version or the other is performed; however, this performance saw an amalgamation of the two. This creation of a new version of Verdi’s work might be considered either innovative or musicologically messy. Regardless, it further complicates the relationship between source work and adaptation that is, for better or worse, always at play in Shakespeare-based opera.

... (read more)Comparisons can be odious, odorous, even otiose. Yet while I have lost count of the number of takes on Shakespeare’s play I have seen over the years – theatre, ballet, modern dance, knockabout collages of dance, movement and music, and opera – five stay in the memory. In the order in which I saw them, they are: the first revival at Sadler’s Wells in the mid-1960s of Britten’s 1960 opera, which marked the beginning of James Bowman’s stellar career; Max Reinhardt’s 1935 film; Peter Brook’s version of the play, which redefined it for not just one but several generations; Elijah Moshinsky’s powerfully evocative take on the opera from 1978 (also starring Bowman); and Declan Donnellan’s inspired and laugh-out-loud shaking up of the work for the Donmar Warehouse in the mid-1980s.

... (read more)