Living in a Modern Way: California Design 1930–1965 edited by Wendy Kaplan

Living in a Modern Way:California Design 1930–1965 is the catalogue accompanying an exhibition of the same name at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art in 2011–12. The exhibition is now showing at Queensland’s Gallery of Modern Art, after a stint in Seoul.

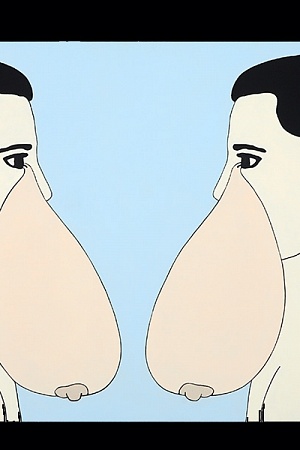

With its stylish dust jacket, based on a 1956 record cover by Paul Bass, California Design proclaims the subject’s characteristics from the outset: clean lines, strong colours, modernism, commercialisation. The complex reasons for the emergence of a peculiarly Californian design character from 1930 to 1965 are comprehensively explored in this superbly designed and copiously illustrated volume. The influence of this regional form of modernism, one that largely celebrates the Californian ideal, has been international. Nowhere has its influence been felt more strongly than in Australia.

Continue reading for only $10 per month. Subscribe and gain full access to Australian Book Review. Already a subscriber? Sign in. If you need assistance, feel free to contact us.

Leave a comment

If you are an ABR subscriber, you will need to sign in to post a comment.

If you have forgotten your sign in details, or if you receive an error message when trying to submit your comment, please email your comment (and the name of the article to which it relates) to ABR Comments. We will review your comment and, subject to approval, we will post it under your name.

Please note that all comments must be approved by ABR and comply with our Terms & Conditions.