Degenerate Art (Red Line Productions) ★★★

In the middle of Adolf Hitler’s speech to the assembled faithful on the final evening of the 1934 Nuremberg Rally which is the culmination of Leni Riefenstahl’s film Triumph of the Will, the führer conjures up a particularly heartfelt bellow from the gathering. For a moment he looks down at the podium with a smirk and a slight shrug, as if to say, that went down well. Here, we can see him as a performer who is pleased that his act is working. As far back as the 1930s, both Charlie Chaplin and Bertolt Brecht saw Hitler as a mountebank – part evil, part ridiculous – who played upon the shattered pride of a defeated nation. Famously, according to Luis Buñuel, Chaplin fell of his chair laughing when watching Riefenstahl’s opus.

As well as being a rather ham actor, Hitler considered himself a connoisseur of the arts. His inability as a young man to gain admission to an art school didn’t dent his self-image as an artist manqué. Other than his overriding obsession with Richard Wagner, his taste in the arts, like that of his fellow dictator, Josef Stalin, a would-be poet in his youth, was strictly middlebrow.

When the Nazis took control, it was not only works with a Jewish connection that needed to be weeded out: it was anything that might challenge Nazi ideology or cause the masses to think. The literary scholar Ernst Bertram composed a lyric to be sung at the infamous night of the Berlin book burning on May 10th 1933. In part it could sum up every autocracy’s demands of its subjects: ‘Reject what confuses you / Outlaw what seduces you, / What did not spring from a pure will, / Into the flames with you.’

In 1937, Joseph Goebbels, failed novelist and minister for propaganda, as a warning to the masses and a counterpoint to the current Great German Art Exhibition, had an exhibition of forbidden artworks curated under the title Entartete Kunst (Degenerate Art). Given the choice between acres of romanticised German landscapes and endless pictures of muscular blonde youths gazing meaningfully into the distance and an exhibition that promised titillation, it is no surprise which was the greater success.

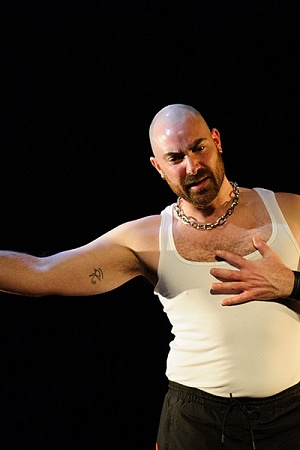

Henry Dixon and writer, director, and actor Toby Schmitz in Degenerate Art (photo by John Marmaras)

Henry Dixon and writer, director, and actor Toby Schmitz in Degenerate Art (photo by John Marmaras)

Toby Schmitz has given himself some fertile ground to explore. How can the persuasive power of the arts be used to poison the minds of an entire nation? Is there such a thing as degenerate art? If so, is it George Grosz’s images of rapists and murderers, or is it Josef Thorak’s overblown, monumental sculptures glorifying the Nazi’s Aryan obsession? Or can we see the Nazi leaders themselves as degenerate artists creating their own monstrous updating of Gotterdammerung?

Unfortunately, though Schmitz touches on these themes in his wildly overwritten, over-heated play, none of them is fully developed.

When presenting the Nazi leadership, Schmitz makes the wise decision not to attempt any impersonation. His actors are dressed in identical dark suits, and no effort has been made to make them physically resemble the historic characters they portray. The tall, imposing Schmitz looks nothing like the miniscule, club-footed Goebbels. This would not have mattered had Schmitz explored their personalities, but, with one exception, he shows them mainly as a bunch of buffoons squabbling over the spoils of conquest. We see nothing of Goebbels, the consummate master of propaganda – only Goebbels the producer of a disastrous film about the Titanic.

Giles Gartrell-Mills, Henry Nixon, and Toby Schmitz in Degenerate Art (photo by John Marmaras)

Giles Gartrell-Mills, Henry Nixon, and Toby Schmitz in Degenerate Art (photo by John Marmaras)

Schmitz is out to make the not entirely ground-breaking point that these were ordinary, educated, even, to a certain extent, cultivated men, who were capable of committing appalling atrocities. Cut through the thickets of verbiage and we are back to the well-used image of the camp commandant playing Beethoven sonatas while smoke rises from the camp chimneys.

The one exception to the interchangeable chorus of vicious clowns is the one survivor. In Albert Speer, Schmitz presents us with a cool, calculating opportunist of vaulting ambition, happy to play along with a leader who provides him with an inexhaustible supply of slave labour to fulfil his ambitions. Septimus Caton sinks his teeth into the role, developing from a nervous, overwhelmed young man, to a man glorying in his power and, finally, to an ironic observer of the final catastrophe. In Wagnerian terms, he is the Loge of the piece. Not a member of the inner circle, he can see through the megalomania but will play along for as long as it suits him. The scenes between Speer and Henry Nixon’s Hitler, fantasising about the dream cities he intends to build as the Third Reich crumbles around him, are the most effective in the play.

Henry Nixon, Megan O'Connell, and Giles Gartrell-Mills in Degenerate Art (photo by John Marmaras)

Henry Nixon, Megan O'Connell, and Giles Gartrell-Mills in Degenerate Art (photo by John Marmaras)

Schmitz has his actors play mostly at a deafening volume. We know that ranting was something of a Nazi speciality, but it is a relief to hear the calm voice of Megan O’Connell’s narrator, who supplies us with historical background.

With admirable ambition, Schmitz has taken on a formidable subject. It is a pity that that ambition is not entirely fulfilled.

Degenerate Art, written and directed by Toby Schmitz. Presented by Red Line Productions at the Old Fitz Theatre from 17 October to 4 November 2018. Performance attended: October 23.

ABR Arts is generously supported by The Copyright Agency's Cultural Fund and the ABR Patrons.

Leave a comment

If you are an ABR subscriber, you will need to sign in to post a comment.

If you have forgotten your sign in details, or if you receive an error message when trying to submit your comment, please email your comment (and the name of the article to which it relates) to ABR Comments. We will review your comment and, subject to approval, we will post it under your name.

Please note that all comments must be approved by ABR and comply with our Terms & Conditions.