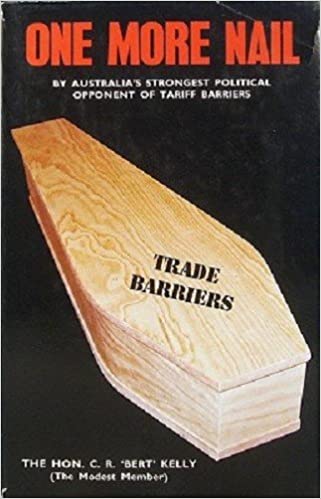

One More Nail

Brolga Books, 231 pp, $9.95

The Politics of Tariffs

Bert Kelly has had three careers and one idea. He was a farmer by inheritance and turned himself into an agricultural whiz who could pick flaws in subsidised projects from the Ord River to Kathmandu. He was a federal politician for eighteen years, holding the blue-ribbon Liberal seat of Wakefield and scraping a couple of ministries under John Gorton. And he has become widely known as a folksy columnist, writing as ‘The Modest Member’ and since his departure from Canberra in 1977 as ‘The Modest Farmer’, amongst other pseudonyms.

Pursued through his three careers, Kelly’s idea was that tariffs on manufactured goods should be lower. This would make life easier for farmers, even if it throws other people out of jobs. It has lately had a powerful pull among other people, too: those who have tenured jobs financed out of the general revenue; and there have been visionaries who see the ultimate abolition of tariffs as a way of gelling rid of manufacturing altogether.

In One More Nail, the plea for low tariffs appears between hard covers, along with a diary of the author's days in Nepal and a collection of political anecdotes.

But Kelly was more than a man with one, fixed idea. He was a close student of the Tariff Board and its successor, the Industries Commission, and he was a party to many of the moves surrounding trade policy. I turned to his book for an account of these manoeuvres, hoping that a man who has left professional politics might feel free to paint an unvarnished picture, but I closed it in disappointment. Something had been missing from his understanding of the situation all along. Coming from South Australia where the choice is Liberal or Labor he hasn’t managed to appreciate the precarious existence of the Country Party, and the ruses its leaders have had to indulge in for survival.

The conflict of interest between farmers and manufacturers has wide, and often hidden, political ramifications. It was noted, way back, by Adam Smith in The Wealth of Nations. British manufacturers wanted cheap, imported cereals to keep down wages, and under the banner of free trade, they won the battle against the domestic farmers. The rise of Britain as a manufacturing nation gave free trade a high reputation. In countries which industrialised later, such as Germany and Italy, a political compromise was struck over tariffs. By the late nineteenth century, the demands of rising socialist movements preoccupied landlords and industrialists, and they got together under a variety of formulae expressing the trade-offs on which they had agreed.

The conflict between Australian agrarian and manufacturing interests was a mirror image of the British situation. The parties were similar, but their bread was buttered on opposite sides. Our farmers, who did most of the country’s exporting, wanted cheap industrial goods and adopted the ready-made free trade doctrine. Our manufacturers relied on the domestic market, and wanted tariff barriers. They may have glanced at German or American protectionism, but Britain was the fount of economic wisdom, and by the Australians looked across the Pacific in awe, Coca-Cola had begun to permeate the globe and the flag of free trade was flown at American universities from Boston to Chicago.

As in so many matters, consistent doctrine on international trade counted little with politicians. The important thing was to gel the issue well out of the way, to institutionalise public controversy. The device used was the Tariff Board. In the decade after World War I, when the Country Party began to represent ‘the man on the land’ and the predecessors of the Liberal Party counted the new, large manufacturers among their mainstays, tariff policy was a hinge round which coalitions swung. The swing could not go too much this way, too far the other. The Tariff Board was useful in absorbing untimely pressures. What if a manufacturer in a swinging electorate mounted an intense campaign for protection? The general level of prices was not likely to be affected, so the matter was refer red to the Board in the hope of its ultimate support. But what when a strong lobby, with an output used in many branches of industry, mounted a concerted drive? It was shunted off into a complex inquiry lasting till the next election was over. The coalition held together; its backers were encouraged to hold their dogfights in a well-regulated backyard.

This cosy arrangement started to come to pieces when the Menzies government, having scrapped import quotas, met its balance of payment problem by sharply reducing demand. To pick up the pieces after the recession poll of 1961, John McEwen, as Minister for Trade, pressed for higher protection. The chairman of the Tariff Board, Sir Leslie Melville, relinquished his post in dismay and McEwen filled the Board with senior officers from his Department. By the mid-1960s, he was so well regarded by the beneficiaries of his policies that Sir James Kirby, a Sydney manufacturer, headed an appeal for funds to build McEwen House, the Canberra headquarters of the Country Party.

Bert Kelly welcomed the abolition of import quotas and in 1960 called for a recession nine months before the Treasury recommended it and the Government followed its advice. The new McEwenism, which emerged in the wake of this disaster, spurred him to great efforts: in one adjournment debate, he spoke four times against protection. He kept a diary of his doings, but One More Nail reveals next to nothing about them. The reader is rationed to one incident. Kelly took to Menzies a newspaper cutting of a protectionist speech by McEwen. Menzies pondered it for three weeks and then called the member for Wakefield back into the presence: ‘He handed the cutting back and said: “Use it when and how you like, my boy, I am sick of the sod”.’

Dropped from the Gorton Ministry, Kelly began to write for the Australian Financial Review. For his weekly column invented Eccles, a character whose opinions closely resembled those of Richard Boyer, the woolgrower and Tariff Board member who had converted Alf Rattigan, his chairman, to free trade. When Whitlam made the Tariff Board over into the sumptuous Industries Assistance Commission, Peter Robinson, Kelly’s editor, joined it. The Commission began to play a new role. Where crude politicians attacked strikers, it played a long game. It flooded the market with imported goods, thus cutting the unions down to size before they could mount their claims.

Encouraged by their success, some members of the Commission have begun to lecture the country on performing arts and on the wastefulness of subsidies to publishing. These run to a small fraction of the Commission’s lavish budget.

On all these events, Kelly is silent. The low-tariff mafia has its own code of honour, and for the real effect which the ‘Modest Member’ had on our lives, we’ll have to await the posthumous release of his diary.

Leave a comment

If you are an ABR subscriber, you will need to sign in to post a comment.

If you have forgotten your sign in details, or if you receive an error message when trying to submit your comment, please email your comment (and the name of the article to which it relates) to ABR Comments. We will review your comment and, subject to approval, we will post it under your name.

Please note that all comments must be approved by ABR and comply with our Terms & Conditions.