Danielle Clode

Every Living Thing: The great and deadly race to know all life by Jason Roberts

by Danielle Clode •

Big Meg: The story of the largest and most mysterious predator that ever lived by Tim Flannery and Emma Flannery

by Danielle Clode •

Goldfish in the Parlour: The Victorian craze for marine life by John Simons

by Danielle Clode •

The Plant Thieves: Secrets of the herbarium by Prudence Gibson

by Danielle Clode •

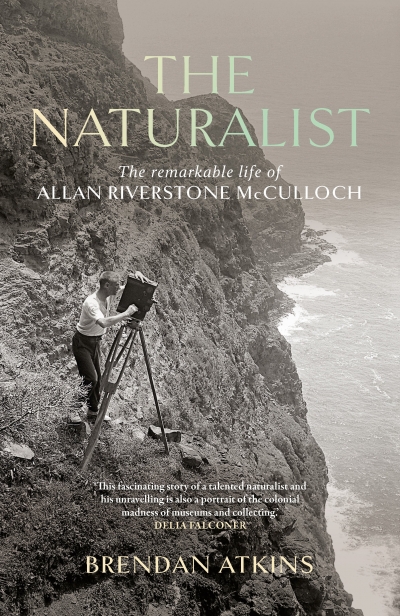

The Naturalist: The remarkable life of Allan Riverstone McCulloch by Brendan Atkins

by Danielle Clode •

Rose: The extraordinary voyage of Rose de Freycinet, the stowaway who sailed around the world for love by Suzanne Falkiner

by Danielle Clode •

I enjoy critics who read beyond the content of the book to discuss what they think the book or author is trying to achieve. Even better if they discover that the book does something the author wasn’t expecting or didn’t deliberately plan.

... (read more)