Aesop the Fox

Spinifex, $24.95 pb, 129 pp, 9781925581515

Aesop the Fox by Suniti Namjoshi

Suniti Namjoshi has made an international reputation as a fabulist and poet with a strong feminist bent. Some Australian readers will be familiar with her work, long published here by Spinifex. Another Australian connection: after leaving India, then Canada, Namjoshi settled in England with her Australian partner, the writer Gillian Hanscombe.

Being a fabulist is not a common occupation for present-day writers, even a touch anachronistic, but in Namjoshi’s hands the fable expands to encompass facets of modern life and is used to re-examine fundamental values and concepts. This is all done with the lightest of touches and a sly, whimsical sense of humour. Namjoshi has a voice like no other: playful, gently satirical, backed by a depth of knowledge of European literature, and enriched by myths and fables of many cultures.

In Aesop the Fox, Aesop the man is elided with his well-known Fox fable. The conceit is that Namjoshi, longing to meet her famous predecessor, time travels to sixth-century-bce Greece to find out more about him. After all, he is as famous, in his way, she says, as Homer or Shakespeare. When Namjoshi turns up, Aesop and his young friend Androcles – of Androcles and the Lion fame – are slaves, owned by a nasty character who breaches his promise to free them. Instead, he sells them on to a much more humane master, Jadmon. In their new home, Androcles finds favour with his pleasing singing voice, and the master likes Aesop’s stories, and so asks him to tutor his children. It is not long before the slaves are given their freedom but choose to stay with this pleasant household.

During these happier times, the narrator pesters Aesop for the meaning of his fables and their ultimate aim. But she is rarely successful. Despite the fact that Aesop has ‘yanked’ her back to his time to observe him, he is not very cooperative, even morose:

He tells me to be quiet. He says, ‘You are, after all, only a figment of my imagination, hauled in from the future.’

‘And you and your fables,’ I retort, ‘are only a figment of everyone else’s imagination. Nobody knows who you really are.’

The narrator is invisible to people, but is heard by those who tune into her. They call her Sprite, which she hates – and later, Tipon, the Greek version of a TPN, or a Third Person Narrator.

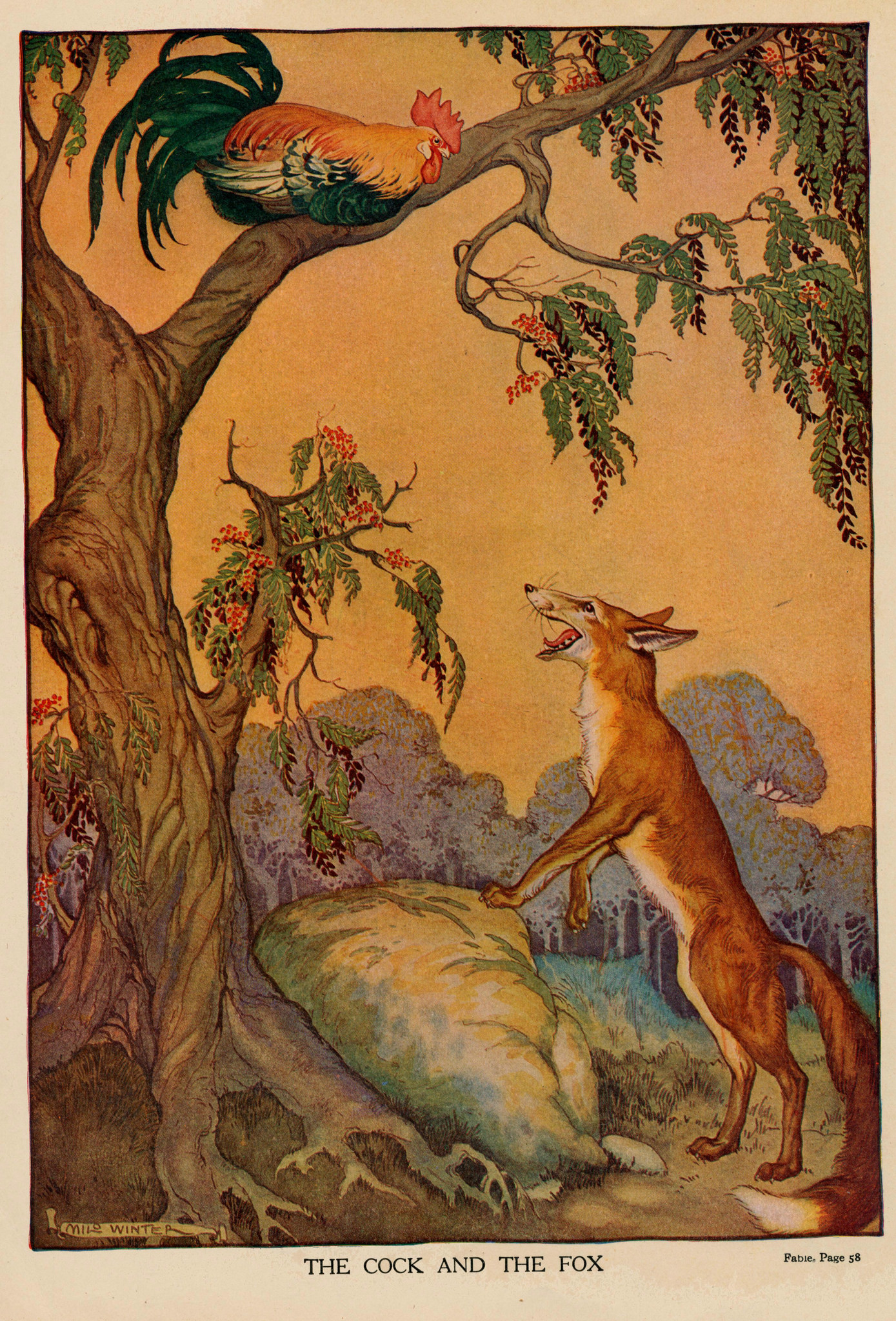

The Cock And The Fox by Milo Winter, 1919.As we progress through this small book, we are informed, teased, and challenged all at once. We get to know the sketchy facts, many contested, of Aesop’s life. He was probably born in India, or possibly Egypt. Namjoshi, of course, roots for India. He is brown, not black, as some people have thought. And much of his life is spent in slavery on the island of Samos.

The Cock And The Fox by Milo Winter, 1919.As we progress through this small book, we are informed, teased, and challenged all at once. We get to know the sketchy facts, many contested, of Aesop’s life. He was probably born in India, or possibly Egypt. Namjoshi, of course, roots for India. He is brown, not black, as some people have thought. And much of his life is spent in slavery on the island of Samos.

A picture emerges of life in the sixth century BCE: earthen floors, a monotonous diet of fish, chickpeas and bread, goats tethered by the door, basic dormitories for the slaves, their only possession a bit of bedding. Athens on the mainland is a dusty rundown town, before it hit its glory days a few centuries later.

As Sprite is in on all conversations, she gets to meet the famous young Pythagoras (even though Namjoshi cheerfully admits to stealing him from another time). They have a stimulating discussion about the ‘metempsychosis’ of souls – the sixth-century-BCE version of time travelling. All this is informative and entertaining, but deeper meanings and questions are always lurking. When the talk falls to the difference between men and women, Pythagoras is unabashedly a young glib male, putting down women without thinking. ‘Aesop and Aglaia, [Jadom’s wife] glance at each other. They are both appalled. Perhaps women and slaves have something in common? Dependence. Powerlessness. And Fear. Bright Sprite! I knew all that. Didn’t have to go back to the sixth century B.C. Suddenly I’m cross with myself. What do I want from Aesop?’

So she tests the ideas of twentieth-century feminism on Aglaia, beautiful and intelligent, and content with her lot. Aglaia is puzzled by the questioning, but as discussion deepens, Sprite understands that Aglaia is a strategist and deep down already a feminist. ‘I’m silenced. Perhaps Aglaia doesn’t need to have her consciousness raised. Perhaps she already knows a thing or two.’

All the way through, different versions of fables are discussed and interpreted: how you can fit different morals to a story and vice versa. Are the fables just cautionary tales or are there stronger moral and intellectual dimensions?

When local politics change dramatically in Samos, Jadmon has to make a crucial decision: which side should he be on? The Sprite can tell him what the history books say, so, in order to curry favour with the new ruler, Jadmon travels with Aesop to Delphi to deliver some treasure for the priests. My attention waned with the particulars of this journey until I grasped Namjoshi’s drift. She tells her characters that some ‘unreliable’ future accounts say that Aesop was thrown off a cliff and killed at Delphi. So it is up to her, as the ‘Tipon’, to change this tale, if she wishes. She has many doubts: this narrator is a more ‘doubtful’ Third Person Narrator than an ‘unreliable’ one.

As we are in Ancient Greece, the text sometimes reads like an alternative Socratic dialogue. But the voice is a more feminine one: unwilling to trade in absolutes, wanting to hear the legitimate claims of other voices, always questioning her central function to control or manipulate the narrative. In the end, she contrives to postpone Aesop’s death: a happier ending. But Aesop packs Sprite to back to her own century with many questions unanswered. She wants a role for truth and justice and progress, but Aesop is not interested. When she is gone, he says, he will be free:

‘Free from what?’

He looks surprised, as though the answer should be obvious. ‘From you, Sprite. From your unreliable books and prescriptive fantasies. From your wanting to confine me and my work to a fixed, unalterable thing. We live in time, Sprite. Don’t you understand? The dream mutates and shifts.’

And he hurls her back to her own ‘broken world’.

What ‘moral’ are we to take away? Let the fable speak for itself. Each reader in each place and time will have his or her own meanings. ‘The fables remain – some of them anyway – repeated, mutated, fizzing with energy.’

Leave a comment

If you are an ABR subscriber, you will need to sign in to post a comment.

If you have forgotten your sign in details, or if you receive an error message when trying to submit your comment, please email your comment (and the name of the article to which it relates) to ABR Comments. We will review your comment and, subject to approval, we will post it under your name.

Please note that all comments must be approved by ABR and comply with our Terms & Conditions.