The Shape of Sound

Text Publishing, $34.99 pb, 297 pp

Out of the shadows

More than twenty-five years ago, I wrote an essay on the work of Oliver Sacks (Island Magazine, Autumn 1993). Entitled ‘Anthropologist of Mind’, it ranged across several of Sacks’s books; but it was Seeing Voices, published in 1989, that was the main impetus for the essay. In Seeing Voices, Sacks explored American deaf communities, past and present. He exposed the stringent and often punishing attempts to ‘normalise’ deaf people by forcing them to communicate orally, and he simultaneously deplored the denigration and widespread outlawing of sign language. Drawing on the work of Erving Goffman, Sacks showed how deaf people were stigmatised and marginalised from mainstream culture, and he revealed, contrary to prevailing opinion in the hearing world, the richness and complexities of American Sign Language.

I was first diagnosed with a hearing loss at the age of twenty-eight. At the time, I was working as a speech pathologist. Any degree of deafness is somewhat of a liability for a speech pathologist, so it was fortunate that my primary passion was fiction. Owing to my strenuous attempts to hide it, no one knew about my hearing problems, and that remained the case for several decades. All those years ago I welcomed Sacks’s book, as I now welcome Fiona Murphy’s The Shape of Sound.

Hearing loss is perceived differently from short-sightedness, and hearing aids carry a stigma not applied to spectacles. If you can’t hear properly, it is often assumed you cannot communicate. Until recently, deaf people who did not communicate orally, and even some who did, were described as deaf and dumb. I always wanted to avoid that stigma.

And so did Fiona Murphy.

Murphy was born in 1988. She was, from birth, profoundly deaf in her left ear, although this was not discovered until she was five years old; her hearing in her right ear was within normal range until her thirties when she was struck by the double unfairness of tinnitus (a constant noise in her ear) and otosclerosis in her right ear, a relatively rare condition that leads to loss of hearing.

Murphy’s hearing loss infused her identity from the time she started school. Was she deaf? Half deaf? Half hearing? Although given her attempts to pass as not deaf, the specific description is probably immaterial. Murphy, like me, and like so many deaf people, had absorbed the negative associations that prevail about hearing loss.

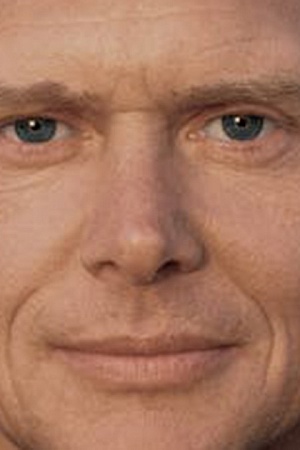

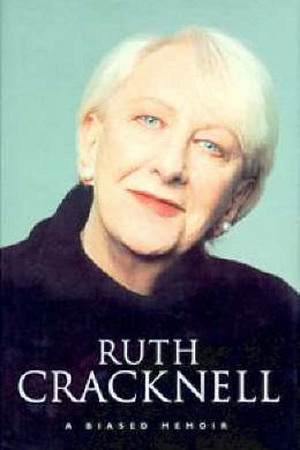

Fiona Murphy (photograph via Text Publishing)

Fiona Murphy (photograph via Text Publishing)

Murphy was an intelligent, curious child, with a strong desire to communicate. She hid her deafness at school, and believed she was passing successfully; so when someone asked about her accent, she was shocked to learn she had one. It was only when Murphy recalled that she learned to read and sound out words with her Irish mother that the accent became explicable. She was a teenager when her brother, in exasperation, told her to stop talking in fragments. Murphy talked the way she heard, and she heard in fragments: because of her hearing loss, she was picking up only scattered words in an utterance and filling in the gaps herself.

She relied on lip reading, but was unaware of this until she was twenty-seven and set herself a test in a noisy bar. It was impossible to ‘hear’ if she could not see the person’s face (and, I might add, impossible in these days of Covid-19 and masks).

In her late twenties, Murphy was fitted with a specialist CROS hearing aid, which would re-route the sound and give her the sense of hearing in her left ear. But the world was so noisy, intolerably so, that she returned the aid after two weeks. I wonder why the audiologist set the loudness level so high. When I was fitted with hearing aids, it took almost two years for the sound to be turned up to the level of normal hearing. Even now, on those rare occasions when I go into the world wearing my aids, I can’t abide the howling wind, the roaring cars, people shouting into their phones.

Few people are totally deaf, many are partially hearing. Murphy shows what it is to live with hearing loss. She trained as a physiotherapist, she worked in a variety of settings, and she managed. She lived in share houses, she had friends: she managed. She had a loving supportive family: she managed. But life for her had a different dynamic and carried vastly different stresses than for a fully hearing person. For most people, their main energies in conversation go into the engagement, the to and fro of talk, into understanding what is said and responding in a way that moves the conversation forward. For people with hearing loss, the main energies go into actually hearing what is said, and it is exhausting. And you have to be so adept: you hear maybe thirty per cent of the words, you fill in the gaps, you absorb the meaning, you rummage around for an appropriate response, then you speak – all done without pause. It’s hard work and it’s no wonder that Fiona Murphy, and other hearing-impaired people, embrace solitude and silence.

Murphy’s personal story is one that reaches out to deaf and hearing people alike. It reveals the toils of stigma, the effects on one’s identity, the toll it exacts on social life. However, several times through the book her story is interrupted by far less interesting theorising – about secrets, about the body’s involvement in communication, about stigma itself. The book is at times repetitive, and more attention from an editor would have eliminated the heart pantings and sweaty armpits and other physical twitches that Murphy has substituted for complex actions and emotional states. Similarly, there are some clumsy expressions and the occasional typo.

These issues aside, Murphy shines when she’s writing her own experience. Her decades-long struggle to pass as not deaf is vividly portrayed, and late in the book she refers to ‘the vast and shocking amount of mental space I devoted to trying to be nondisabled’. She shows through her own personal history what it is to carry a secret that impinges on every single interaction, every single day of one’s life. Also illuminating is her account of the ‘intimacy’ of Auslan (Australian Sign Language), and her pleasure in learning to sign.

These days, deaf children are absorbed into mainstream schools. Auslan is taught to both hearing and deaf people. One of the few positive features of the pandemic is the presence of someone signing alongside the politicians and medicos during their daily updates. Deafness is being brought out of the shadows and into the public realm. With these changes, and with personal stories like Fiona Murphy’s, deaf children of the future should enjoy lives free of burdensome attempts to pass.

Leave a comment

If you are an ABR subscriber, you will need to sign in to post a comment.

If you have forgotten your sign in details, or if you receive an error message when trying to submit your comment, please email your comment (and the name of the article to which it relates) to ABR Comments. We will review your comment and, subject to approval, we will post it under your name.

Please note that all comments must be approved by ABR and comply with our Terms & Conditions.