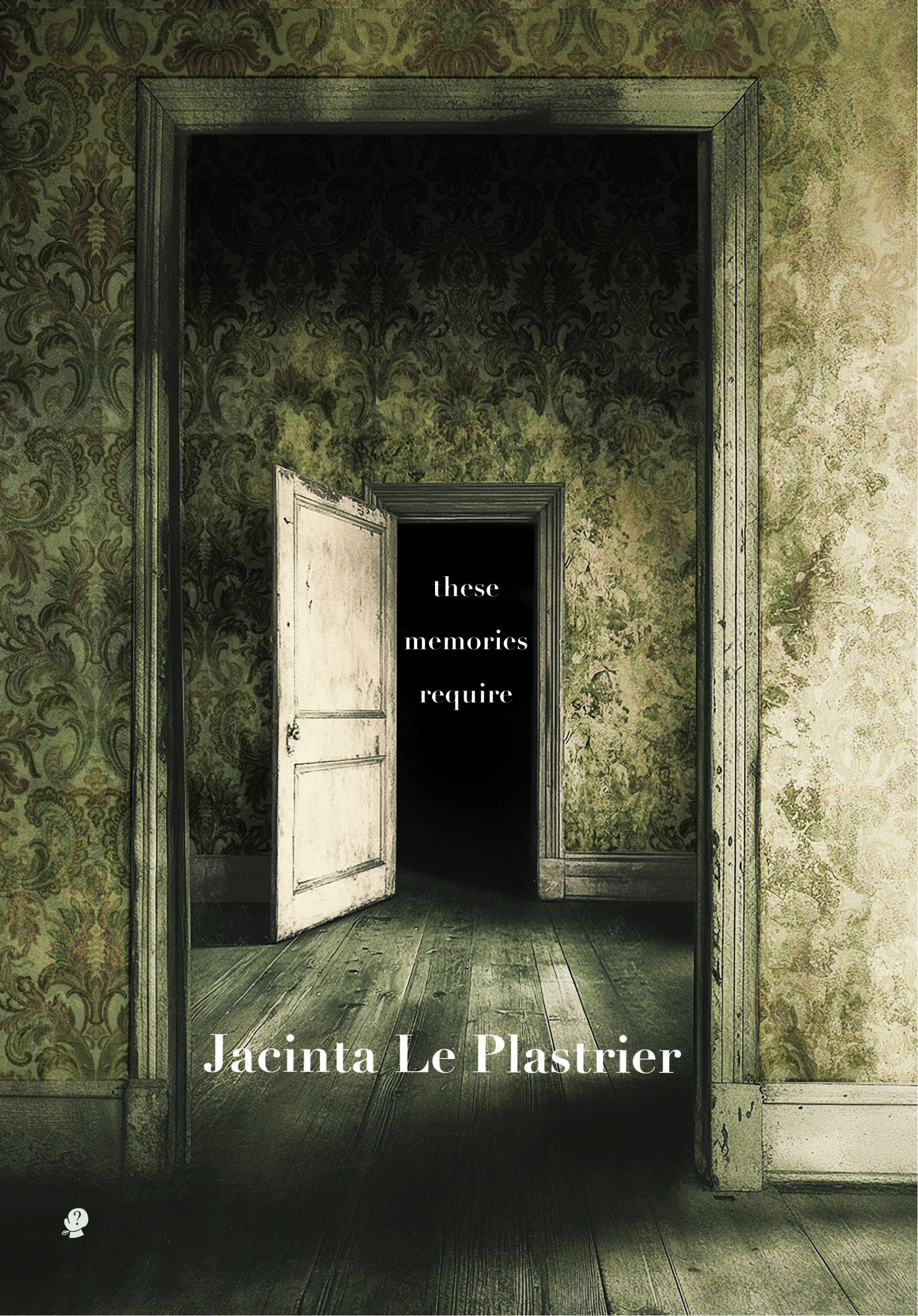

Totality

Recent Work Press, $19.95 pb, 136 pp

Terror hour

Trauma is often said to be unspeakable. There are various reasons for this. Pain and shame are silencing, as are implicit forms of censorship (of the kind scorning trauma literature, for instance) and explicit injunctions against speaking (from perpetrators, enablers, or the law). But it is also the case that trauma doesn’t inhere in language. Trauma lives in the limbic system, which is that of the fight, flight, or freeze response, and which is necessarily more immediate than language processing. After all, when your life is under threat, it’s not words you need, but action.

This is also how trauma can become a kind of puppet master, dictating how a victim responds to perceived threat well beyond the experience of original trauma. In fact, it is only by translating traumatic experience into language that the victim can gain agency. So-called talk therapy helps victims to name and rationalise trauma’s formidable hold, and to intervene when trauma begins to enact its hidden and unbidden agendas. What this means is that correlating trauma with the unspeakable is also highly problematic. Trauma must be spoken.

In the public sphere, Anders Villani has proven extraordinarily articulate, courageous, and generous in speaking about his experience of sexual abuse as a child and young adult. Indeed, his rejection of trauma’s unspeakability in the media functions as a powerful form of activism. In his poetry, however, Villani is less interested in defying than in capturing the silencing force of trauma.

In Totality, Villani’s second poetry collection, trauma is represented as an experience characterised by repression. This becomes apparent through the cryptic nature of many of the poems, which often rupture the quotidian details of autobiographical experience – growing up with an Italian grandmother and embarking on early relationships – with suggestions of sexually charged trauma. Some poems seem surreal in their use of oblique, highly personal imagery – in ways that resonate with the autobiographical mythopoeia of Sylvia Plath – as well as in their employment of incantatory repetition. In the opening poem, ‘To the All-Powerful’, we see Villani’s taste for both elliptical personal imagery and anaphora:

Climb the bunk ladder and make me selfish.

How many birch sprigs should I gather?Climb the bunk ladder and make me selfish.

How many cypress sprigs should I gather?Make me selfish. Grant me a founding.

How many birch sprigs should I gather?The millipede wishes to wake a spiral.

How many cypress sprigs should I gather?

However, demonstrating stylistic range, this collection also contains more accessible narrative poetry. In the brilliantly edgy ‘Map to Mutable Manhood’, the poet remembers the violent sexual boasts of male friends, their ‘legends’ designed to be ‘sung on 4-chan forums’, and reflects on how even his own victimhood is bound up with complicity: ‘men / hurt by a patriarchy that means they could hurt / devilled by that potentiality’.

‘Gunnamatta’ provides another example of the power of narrative clarity. The poet recounts (using the distancing effect of a third-person point of view) an excursion to the tip as a boy with his father, having been promised ‘a trip to Gunnamatta to watch the surfers // once the trailer was emptied’. The poem begins innocuously: ‘They drove to the Rye landfill, / he and his father. The yard waste / they’d loaded overtopped the hired / trailer’s cage, disabling the rear view.’

Bored, the young poet ‘skipped to the junkyard store’ only to discover pornographic videos with ‘naked bodies of ladies and men / posed like he’d been shown’. Here the poem takes a sudden and dramatic turn, showing how even the most bland event can be transformed by the unspoken force of trauma into something terrible.

In ‘Daylesford Fire Bath’, the poet drily acknowledges that his imagery is sometimes ‘too cryptic’ – for this book is nothing if not self-conscious, written more about trauma rather than from trauma, informed by the poet’s research into the subject as part of a PhD. In this poem, Villani suggests that the oblique qualities of his work embody a self-repression that functioned as self-protection: ‘We write the densest / code to firewall ourselves // from ourselves.’ The urge to protect also extends to family members, albeit ambiguously: ‘Spare them / by being dead to them – you get the gist’.

What might be described as the elliptical intention of Villani’s poetry is also acknowledged in the title, Totality, which refers to a solar eclipse and which highlights how the notion of something concealed, if always on the verge of being revealed, structures this book and, indeed, the life of the young poet it represents. The sections of the collection are also named after the phases of a solar eclipse – First Contact, Second Contact, Third Contact, Fourth Contact – with a surprising and superb sequence of sonnets called ‘Moravian Eclipse Myth’ positioned at the book’s centre, the point in the cycle when the eclipse proper takes place. This sequence of poems takes inspiration from ancient myths that story the eclipse. The work is resonant, in its evocation of a fabled world of gothic malevolence, of the poetry of the American poet Charles Simic. Here the figure of the contemporary poet merges with an ancient villager whose quest is to defeat a Cyclops, a monster, driven by a prophecy on a scroll: ‘A kingdom and more for he who slays the ghost / that cannot be slain, whose terror hour is midnight.’

The poem provides an unforgettable image of the trauma survivor as someone haunted by an unspeakable force that can be vanquished only by being named.

Leave a comment

If you are an ABR subscriber, you will need to sign in to post a comment.

If you have forgotten your sign in details, or if you receive an error message when trying to submit your comment, please email your comment (and the name of the article to which it relates) to ABR Comments. We will review your comment and, subject to approval, we will post it under your name.

Please note that all comments must be approved by ABR and comply with our Terms & Conditions.