Review

Cultural Studies Review edited by Chris Healy & Stephen Muecke & Australian Historical Studies edited by Joy Damousi

by Melinda Harvey •

Scarecrow Army by Leon Davidson & Animal Heroes by Anthony Hill

by Margaret MacNabb •

Affluenza: When too much is never enough by Clive Hamilton and Richard Denniss

by Amanda McLeod •

The American Enemy: The history of French anti-Americanism by Philippe Roger

by Colin Nettelbeck •

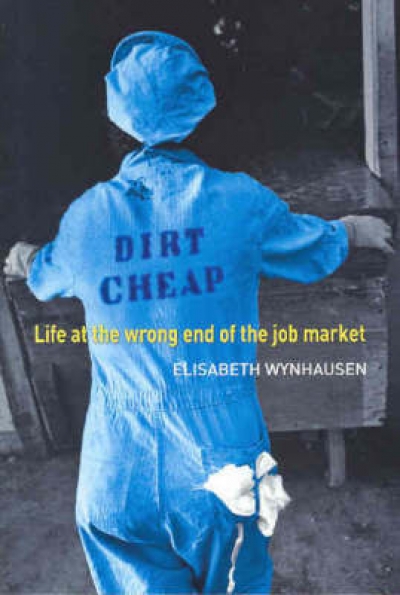

Dirt Cheap: Life at the wrong end of the job market by Elisabeth Wynhausen

by Mark Peel •