ABR receives a commission on items purchased through this link. All ABR reviews are fully independent.

Resisting the Woolfmother

‘I no longer wanted to write novels that read like novels … I wanted a form that allowed for formlessness and mess.’

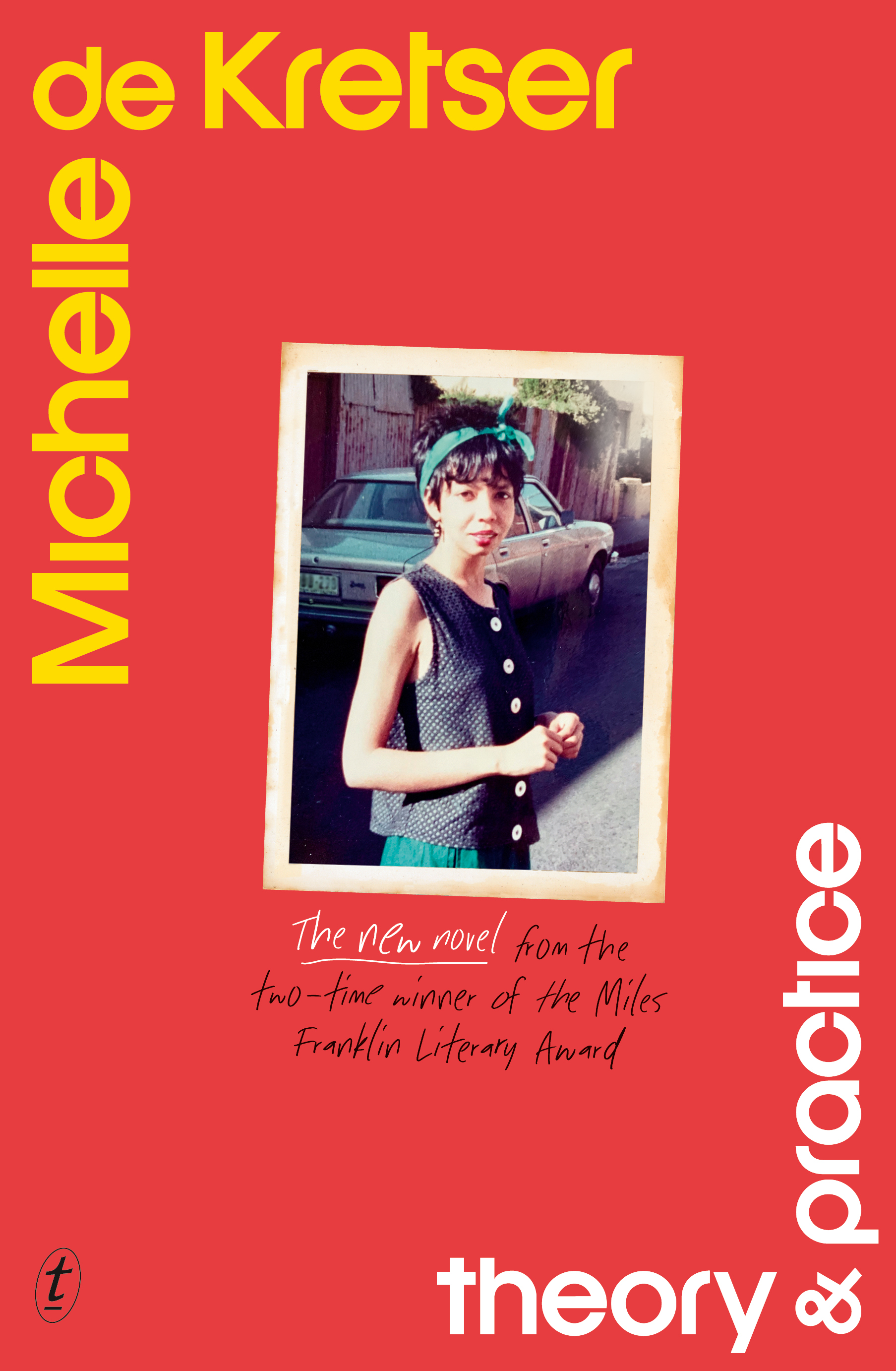

Theory & Practice

How do we reconcile our ideals with the way we live our lives? What should we do when we discover that artists whom we revere turn out to be deeply flawed human beings? How do we continue to love and respect our mothers while acknowledging their shortcomings? Are desire and shame intrinsically linked? Which is the more powerful? These are some of the many issues Michelle de Kretser, twice winner of the Miles Franklin Literary Award (in 2013 for Questions of Travel and in 2018 for The Life to Come) grapples with in her seventh novel, Theory & Practice.

The author has said, in an interview with Books+Publishing, that her starting point was Virginia Woolf’s (unrealised) desire to write a novel combining fiction and essays. De Kretser achieves what Woolf did not, and includes memoir as well, while pointing out that Theory & Practice is not autofiction, because it is mostly fiction, the memoir part being only a ‘splinter’. This is not the first time she has experimented with form in her novels – in Scary Monsters (2021), she (literally) turned the physical book upside down to reflect the upside-down lives of the migrants she was writing about.

Theory & Practice opens with a novel that de Kretser quickly abandons because ‘it wasn’t the book I needed to write’. The book she did need to write ‘concerned breakdowns between theory and practice’. Following short segments of essay, then memoir (in which she describes being sexually abused as a young piano student in Sri Lanka by a British examiner – one of the book’s many examples of the impact of colonialism), she begins.

The novel is set in St Kilda in 1986. Cindy, the twenty-four-year-old narrator, a recent Honours graduate in English and French, arrives in Melbourne from Sydney with a scholarship to do an MA in English. A friend, Lenny, who lectures in Art History, introduces her to bohemian St Kilda and to his circle of arty student friends. These include Kit, who is studying Mining Engineering, and his partner Olivia, who is doing Music and Law. Both have had privileged upbringings, unlike the narrator, a first-generation Sri Lankan migrant who grew up in a rented apartment in western Sydney.

Cindy’s (now ex-) boyfriend has recently cheated on her with a woman called Lois. Irrationally, she feels more hostility towards Lois than towards him, recognising that her jealousy is a ‘trite, despicable emotion … that ran counter to feminist practice’. In Melbourne, she launches into an affair with Kit, feeling nothing but scorn and pity towards Olivia, and deluding herself that she is not responsible for Olivia’s suffering. What matters, she tells herself, is ‘to be fair to myself’. As the affair progresses, she (again) experiences intense sexual jealousy, fantasising about how she might get revenge on Olivia (and failing to join the dots that she is to Olivia what Lois was to her).

This scenario allows de Kretser to explore the discrepancy between the narrator’s feminist principles and how she behaves towards other women in practice. Is it possible, she asks, for a true feminist to feel such loathing and contempt towards a (female) rival? Is sexual jealousy more powerful than female solidarity? This is part of the larger question as to how often people abandon their ideals or moral principles to self-interest. De Kretser also considers the relationship between shame and desire. Cindy is ashamed of her hostile feelings towards another woman, but unable to control them because she is overwhelmed by her desire for Kit.

Another way in which de Kretser demonstrates the gap between theory and practice is through a critique of the writing of Virginia Woolf, the narrator’s literary idol and the subject of her thesis, entitled ‘The Construction of Gender in the Late Fiction of Virginia Woolf’. Reading Woolf’s diaries, Cindy comes across a passage concerning E.W. Perera, who in 1917 came to Britain to notify authorities of atrocities being committed by the British in colonial Ceylon, his home country. Having met Perera in her home, Woolf describes him as a ‘poor little mahogany wretch’ and makes other flagrantly racist observations.

Horrified, Cindy struggles to complete her thesis as she grapples with the difference between Woolf’s public persona as a progressive, highly principled intellectual and her private racism and snobbery. This raises interesting questions about whether it is possible to love the art but loathe the artist – a timeless topic dealt with last year in Clare Dederer’s Monsters and Anna Funder’s Wifedom.

De Krester also examines the complex relationship between mothers and daughters. She has spoken about the ‘push-pull dynamic’ in mother-daughter relationships, in which a daughter needs to ‘find refuge in her mother and escape from her as well’. Throughout the novel, the voice of the narrator’s mother, who lives in Sydney, intrudes via telephone messages in which she vacillates between worrying about her daughter and making her feel guilty for abandoning her. Cindy, who feels responsible for her mother since her father’s death, struggles to break free. She also feels ashamed and embarrassed about her, especially when they mix with educated, privileged white women. In labelling Woolf the ‘Woolfmother’, de Kretser seems to suggest that the narrator needs to break free of her as well.

Early on, Cindy acknowledges that ‘I wanted to join the bourgeoise and I wanted to destroy it.’ This internal conflict recurs when she meets Kit and Olivia and realises how different their backgrounds are from her own. Despite being ideologically opposed to their privilege, she cannot help but envy the ease with which doors open for them. When she learns that Olivia’s father has secured Kit a prestigious job she observes that, ‘a pied-à-terre or a husband, either made a thoughtful gift’ – one of the novel’s best lines.

De Krester deplores the damage that an overly enthusiastic embrace of theory has wrought on the humanities. Lenny laments that ‘artists used to think about art through art. Now they think about it through Theory. What happened to praxis?’ She is particularly concerned at the over-emphasis on theory in the context of literature, portraying a deconstructionist critic as a ‘torturer’, ‘tormenting’ the text to decipher hidden meanings.

Themes of colonialism and racism in both the Sri Lankan and Australian contexts permeate Theory & Practice. In one example, towards the end of the novel, Cindy delivers a paper on Woolf in which she critiques the underlying colonialism in her late novel The Years (1937), which includes an Indian character but gives him no lines – only the white characters have speaking parts. ‘What power has a voice that isn’t heard and respected?’ de Krester asks, in an apparent reference to Australia’s failed referendum.

Theory & Practice is a slim volume at 192 pages, but the ideas contained within it are anything but modest. Michelle de Kretser has deployed fiction, essay, and memoir to powerful effect, showing without telling the ‘messy gap’ and the ‘breakdowns’ between theory and practice.

ABR receives a commission on items purchased through this link. All ABR reviews are fully independent.

Leave a comment

If you are an ABR subscriber, you will need to sign in to post a comment.

If you have forgotten your sign in details, or if you receive an error message when trying to submit your comment, please email your comment (and the name of the article to which it relates) to ABR Comments. We will review your comment and, subject to approval, we will post it under your name.

Please note that all comments must be approved by ABR and comply with our Terms & Conditions.