2024 Arts Highlights of the Year

To celebrate the year’s memorable plays, films, television, music, operas, dance, and exhibitions, we invited a number of arts professionals and critics to nominate their favourites.

Anna Goldsworthy

Three piano recitals for me this year, speaking to the dazzling possibilities of this instrument. In March, as part of the Adelaide Festival’s Daylight Express series, Anthony Romaniuk roamed between grand piano, electric keyboard, and harpsichord in Elder Hall for a kaleidoscopic program spanning from the sixteenth century to Ligeti, and Romaniuk’s own improvisations. It was masterfully curated and vividly performed, offering one possible version of the future of the piano recital. Angela Hewitt stepped out onto that same stage in a gold lamé gown and capelet, performing Mozart, Bach, Handel, and Brahms to a sold-out audience, with her signature dynamism and unruffability (reviewed in ABR Arts, 10/24). It felt like a throwback to the golden age of Margaret Farren-Price’s Impresaria series at Melba Hall. Later that same week, Olli Mustonen joined brilliant colleagues from Europe and Australia for performances of Grieg and his own compositions at Ukaria. Mustonen has a visceral approach to pianism and is a singular compositional voice. For this small captive audience of Adelaide Hills dwellers and chamber-music enthusiasts, it was a revelation.

Diane Stubbings

It will be a long time before I forget MTC’s musical adaptation of My Brilliant Career (ABR Arts, 11/24), one of those rare examples of a theatre production where every element comes together so perfectly that a special alchemy takes place. It won’t be long before its star, Kala Gare, is poached by Broadway or the West End. MTC gave us another winner with Topdog/Underdog (ABR Arts, 8/24). On paper this was a risky production, but with two remarkable performances (Damon Manns and Ras-Samuel), and meticulous direction by Bert LaBonté, it was one of the most staggering and visceral productions of the year. NTLive’s The Motive and the Cue – Jack Thorne and Sam Mendes’s homage to the Burton/Gielgud Hamlet of 1964 – not only celebrated the singular chemistry created when an actor meets a part, it was also a strikingly astute reading of Shakespeare’s play. Special mention to Melbourne’s Red Stitch Theatre, whose superb production of Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? (ABR Arts, 7/24) had a well-earned revival. Two works directed for the theatre by Gary Abrahams – Iphigenia in Splott and A Case for the Existence of God (ABR Arts, 4/24) – showed the extraordinary range and power of this ‘little’ theatre’s work.

Ras Samuel as Booth with Damon Manns as Lincoln (photograph by Sarah Walker)

Ras Samuel as Booth with Damon Manns as Lincoln (photograph by Sarah Walker)

Christopher Allen

Gauguin (ABR Arts, 9/24) at the NGA was outstanding, largely because it was put together by Henri Loyrette, former director of the Louvre, and not by the NGA itself. Magritte at the AGNSW offers a comprehensive overview of the artist’s career. The most substantial contribution to Australian art history was the survey of Charles Rodius at the State Library of NSW, by David Hansen, who sadly died shortly after its opening. Emily Kngwarreye at the NGA was well selected and presented. Emerging from darkness was a thoughtful and scholarly reflection on the Baroque, exiled to Hamilton, while the NGV itself was given over to the year’s worst exhibition, the NGV Triennial. Three substantial Egyptian shows – in Sydney, Canberra, and Melbourne – marked the bicentenary of the decipherment of hieroglyphics.

Paul Gauguin, Parahi te marae (The sacred mountain), 1892, Philadelphia Museum of Art, gift of Mr and Mrs Rodolphe Meyer de Schauensee 1980 (courtesy of National Gallery of Australia)

Paul Gauguin, Parahi te marae (The sacred mountain), 1892, Philadelphia Museum of Art, gift of Mr and Mrs Rodolphe Meyer de Schauensee 1980 (courtesy of National Gallery of Australia)

Julie Ewington

Two extraordinary installations by Aboriginal Australian artists fix 2024 in memory. Archie Moore’s compelling kith and kin – biting, lyrical, sobering, grand in conception, and completely personal – deservedly won the Golden Lion for the best national pavilion at this year’s Venice Biennale. kith and kin will be at Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art (QAGOMA) in late 2025. Don’t miss it. At ACCA in Melbourne, Tennant Creek Brio’s installation of the group’s innovative paintings and videos, grounded in the wisdom of millennia from Warumungu Country, was a joy. Cross-cultural inclusiveness underpins the Brio’s practice, a particularly telling model for this country. I am always grateful for the generosity of retrospective surveys, opportunities to take the measure of a body of work. Among the finest: Brent Harris at AGSA (ABR Arts, 7/24), Adelaide; Rebecca Horn at Haus der Kunst, Munich; Hiroshi Sugimoto at the MCA Australia, Sydney; and Magritte at the AGNSW, this one until early February.

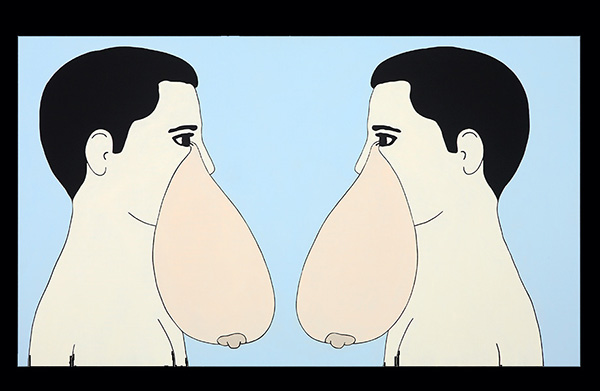

Brent Harris born Palmerston North, New Zealand 4 October 1956 I weep my mother’s breasts 1996, Melbourne oil on linen 57.0 x 96.7 cm; Courtesy of the artist and Robert Heald Gallery, Wellington © Brent Harris

Brent Harris born Palmerston North, New Zealand 4 October 1956 I weep my mother’s breasts 1996, Melbourne oil on linen 57.0 x 96.7 cm; Courtesy of the artist and Robert Heald Gallery, Wellington © Brent Harris

Richard Leathem

On the rare occasion that the Melbourne Recital Centre screens a film, it is to showcase a live score performance. In March this year, the MRC took the unprecedented step of screening a film without any form of live music accompaniment. So exceptional is the Ryuichi Sakamoto concert film Opus that it warrants its presence in a concert hall. Sakamoto prepared the setlist for Opus knowing he did not have long to live. The composer/pianist performed the pared-down renditions of his most loved works alone on a bare soundstage, with no audience. His son, Neo Sora, shot the film in crisp black and white. In a bold move, the MRC charged $45 a ticket. It soon sold out, as did two subsequent screenings. Audiences were rewarded with an immersive experience enhanced by additional speakers installed throughout the acoustically intimate Elisabeth Murdoch Hall. The famously meticulous Sakamoto would surely have approved.

Ryuichi Sakamoto in Opus (courtesy of Janus Films)

Ryuichi Sakamoto in Opus (courtesy of Janus Films)

Peter Rose

The musical highlight of 2024 was the bicentenary of Anton Bruckner’s birth, though you wouldn’t know it from the meagre programming across Australia. It was depressing to read about the Sydney audience’s tepid response to the SSO’s performance of the mighty Eighth Symphony (ABR Arts, 8/24). European orchestras have marked the birthday with concerts of all the symphonies. Kirill Petrenko opened the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra’s 2024-25 season with a revelatory account of Bruckner’s Fifth (not to be missed on BPO’s indispensable Digital Concert Hall). At least the MSO gave us a Beethoven festival, all nine symphonies over five nights, rousingly conducted by Jaime Martín (ABR Arts, 12/24). Matthew López’s epic play The Inheritance has the odd didactic longueur, but Kitan Petkovski’s production at fortyfivedownstairs was audacious theatre at its best (ABR Arts, 1/24). My theatrical highlight of the year was the scintillating revival of Red Stitch’s Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? at the Comedy Theatre (ABR Arts, 7/24). As for opera, nothing surpassed the SSO’s phenomenal concert version of Die Walküre (ABR Arts, 11/24).

David Whiteley, Emily Goddard, Harvey Zielinski, Kat Stewart (photograph by Jodie Hutchinson)

David Whiteley, Emily Goddard, Harvey Zielinski, Kat Stewart (photograph by Jodie Hutchinson)

Robyn Archer

It is always daring to present dancers with disabilities in intimate and erotic contexts. Private View by Restless Dance Theatre represents a highpoint in this company’s achievements. The audience is surrounded by three chambers and observation happens at close quarters. Funny, disturbing, and full of joy, it is all the more moving as the final production to include dramaturg and concept provider Roz Hervey in the creative team. Vale Roz. These dancers are always inspiring, but alongside them this time is singer and composer of all the songs and music, Carla Lippis – a real talent. Eucalyptus, the new opera by composer Jonathan Mills and librettist Meredith Oakes, is a skilful and wholly engaging adaptation of Murray Bail’s novel (ABR Arts, 10/24). Given Mills’s formidable international reputation, it is heartening to note the very Australian themes that have underpinned his compositional work from the start: The Ghost Wife, Eternity Man, Ethereal Eye, and Sandakan Threnody. Eucalyptus is his best yet.

Desiree Frahn as Ellen (photograph by Charlie Kinross)

Desiree Frahn as Ellen (photograph by Charlie Kinross)

Andrew Ford

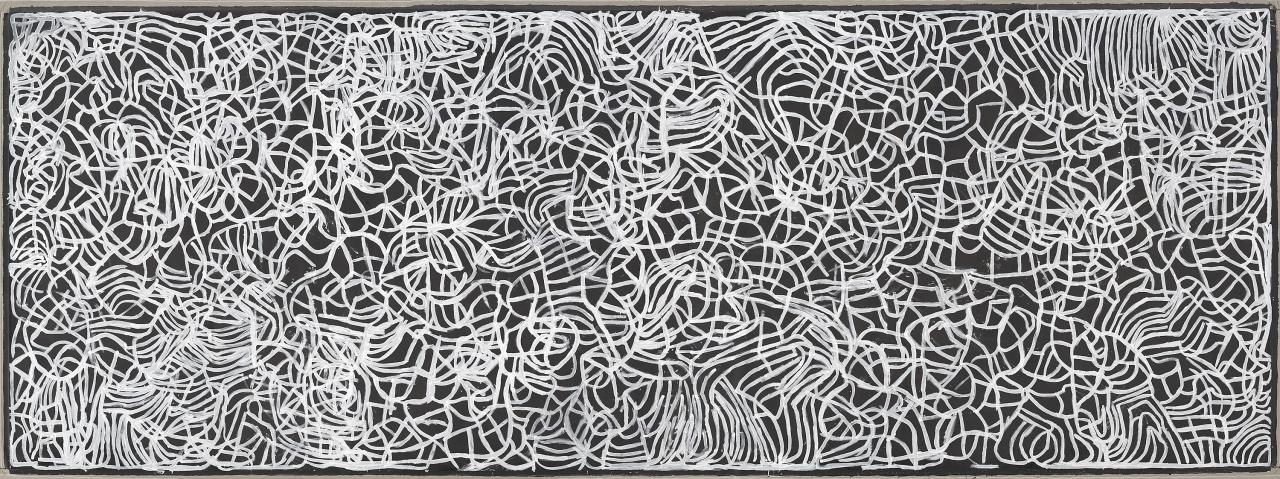

The Emily Kam Kngwarray show at the NGA was far and away my cultural highlight of 2024 – indeed, a highlight of my life. It helped, possibly, that I knew next to nothing of the Anmatyerr artist when I bought my ticket. It was only as I marvelled at the works in the first rooms that the penny dropped that she had begun painting in her seventies. The sheer quantity of her output suggested a lifetime’s dedication to her art. Her technique developed and her style evolved so surely that she seemed to have had an early, middle, and late period – all in the last fifteen years of her life. But it was the sheer artistic ambition that was overwhelming. Glimpsing one of her last works, the eight-metre-wide Anwerlarr Anganenty (Big Yam Dreaming), ahead of me in the final gallery, I gasped loudly – heads turned. I left the show feeling shaken and humbled.

Anwerlarr anganenty (Big yam Dreaming), (National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne Presented through The Art Foundation of Victoria by Donald and Janet Holt and family, Governors, 1995 © Emily Kam Kngwarray/Licensed by Copyright Agency, Australia)

Anwerlarr anganenty (Big yam Dreaming), (National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne Presented through The Art Foundation of Victoria by Donald and Janet Holt and family, Governors, 1995 © Emily Kam Kngwarray/Licensed by Copyright Agency, Australia)

Ian Dickson

Given the surreal chaos that the United States has condemned itself to for the next four years, perhaps the most pertinent offering on Broadway is Cole Escola’s hilarious play Oh Mary!, which envisages Mary Todd Lincoln as a homicidal alcoholic who would happily ditch the position of First Lady to return to her self-proclaimed role as a ‘rather well-known niche cabaret legend’. Escola plays Mary in drag, with a frenetic, superbly timed ebullience. On a more serious note, Gyorgy Kurtag’s compelling operatic setting of Samuel Beckett’s Fin de Partie was given a powerfully effective staging by Hebert Fritsch at the Vienna State Opera. Philippe Sly and George Nigl battled it out as Hamm and Clov, while Charles Workman and Hilary Summers reminisced as Nagg and Nell under the effective baton of Simone Young. Young finished her year in Sydney with a glorious performance of Die Walküre. Both cast and orchestra were in stupendous form, and though it seems invidious to single out special moments, Stuart Skelton and Vida Miknevičiūtė’s first-act encounter as Siegmund and Sieglinde, and Tommi Hakala’s Wotan’s Farewell, will remain in this Wagnerian’s memory a long time.

Simone Young conducts Die Walküre (photograph by Jay Patel and courtesy of Sydney Symphony Orchestra)

Simone Young conducts Die Walküre (photograph by Jay Patel and courtesy of Sydney Symphony Orchestra)

Felicity Chaplin

My year opened with Ludovico Einaudi at the Myer Music Bowl, as part of his tour to promote his then latest album, Underwater. Einaudi did not simply reproduce the pieces on the album but wove them together, along with some of his earlier iconic works to create a soundscape at once familiar and strange. In July, while teaching European cinema at the Monash Prato centre, I had the privilege of attending two very different film festivals: the world-famous Il Cinema Ritrovato held annually in Bologna, and the lesser-known Il Cinema Sotto le Stelle in the Castello dell’imperatore di Prato, a thirteenth-century castle in the centre of the Tuscan city of Prato. A highlight of Ritrovato was attending a rare screening of Luca Guadagnino’s début feature film, The Protagonists (1999), starring Tilda Swinton; and in Prato I was treated to a twilight screening of Italian director Alice Rohrwacher’s 2023 masterpiece, La Chimera (ABR Arts, 9/23).

Josh O'Connor as Arthur (courtesy of Palace Films)

Josh O'Connor as Arthur (courtesy of Palace Films)

Tim Byrne

Melbourne audiences were finally given the opportunity to see S. Shakthidharan and Eamon Flack’s gorgeous Sri Lankan epic Counting and Cracking in the new UMAC theatre, many years after it won the VPLA (full disclosure: I was on the judging panel that year). Expansive, funny, and almost impossibly moving, it was community theatre as divine revelation. Back to Back Theatre returned to Geelong after receiving the Golden Lion award at this year’s Venice Biennale with Multiple Bad Things, a dark, pointed exploration of work and leisure, highlighting the insidious appropriation of disability by the able-bodied. It landed like a silent scream. And MTC rounded out the year with the greatest musical the country may have ever seen, an adaptation of Stella ‘Miles’ Franklin’s My Brilliant Career. An astonishing lead performance by Kala Gare galvanised a brilliant cast, all orchestrated by artistic director Anne-Louise Sarks, recovering brilliantly from her serious misfire with A Streetcar Named Desire (ABR Arts, 7/24).

Kala Gare as Sybylla Melvyn (photograph by Pia Johnson)

Kala Gare as Sybylla Melvyn (photograph by Pia Johnson)

Des Cowley

The Necks’ performance at Brunswick Ballroom in February revealed that, three decades on, their music remains as enigmatic and adventurous as ever. In March, saxophonist Cheryl Durongpisitkul’s ‘Straight Up and Down #1’, composed for the Australian Art Orchestra (AAO) and performed en plein air at Melbourne’s Section 8, was a wild and brawny affair, visceral and intense. Little wonder that Durongpisitkul won Jazz Work of the Year at the 2024 Art Music Awards. In October, as part of the Melbourne International Jazz Festival, Herbie Hancock confirmed his standing as one of our greatest living artists (ABR Arts, 10/24). Aged eighty-four, with nothing left to prove, Hancock continues to produce exciting and innovative music. Finally, the AAO’s thirtieth-anniversary concert at Melbourne Recital Centre in November marked a genuine milestone. The program featured works developed by the AAO over three decades, notably Paul Grabowsky’s Ring the Bells Backwards, his radical reinterpretation of European popular song, and Peter Knight’s hypnotic The Plains, inspired by the Gerald Murnane novel.

Herbie Hancock (photograph by @Duncographic and courtesy of MIJF)

Herbie Hancock (photograph by @Duncographic and courtesy of MIJF)

Ellie Nielsen

In a year which saw a dazzling return of the monologue play, Red Stitch’s production of Gary Owen’s, Iphigenia in Splott was a standout. This stark, unstinting work, bought to blazing life by Jessica Clarke, revealed how intensely the monologue can interrogate the human condition. In contrast, Matthew Lopez’s Inheritance, at fortyfivedownstairs, was the equivalent of a theatrical marathon; a seven-hour long journey with thirteen actors. This bold theatrical leap of faith (from a relatively small, unfunded theatre) went to the heart of what great theatre can be. Similarly, Apologia, created by performance artist Nicola Gunn, and produced by Malthouse, expanded and scrutinised the theatrical space, posing questions about interpretation, translation, and the way we create meaning. Apologia is a witty, absurdist piece, ostensibly a fantasy about being a French actress. Gunn’s cool merger of stagecraft with choreography and visual art, together with her versatile performance, was enigmatic and utterly engrossing.

The Inheritance (photograph by Cameron Grant)

The Inheritance (photograph by Cameron Grant)

Michael Halliwell

A year with two new Australian operas in one year is cause for celebration. Much delayed, Jonathan Mills’s Eucalyptus premièred in Melbourne. Directed by Michael Gow, this ethereally beautiful adaptation of Murray Bail’s enigmatic 1998 novel was greeted with enthusiasm; one hopes for further performances. Mills’s unique voice combines modernism tempered by a lyricism in his writing for voices and orchestra. Young composer and leader of Sydney Chamber Opera, Jack Symonds, added to his already impressive body of work with a musically challenging version of the ancient Mesopotamian legend of Gilgamesh (ABR Arts, 9/24). His music takes no prisoners, plunging the audience into a world of violence and disruption, but ending on an uplifting note. Finally, a brief trip to icy Stockholm offered the opportunity to see a deeply moving operatic love story set during and after the Holocaust. The Promise (Löftet), by Mats Larsson Gothe, is a journey oscillating between dream and reality, hope and despair.

Mitchell Riley as Enkidu and Jeremy Kleeman as Gilgamesh (photograph by Daniel Boud)

Mitchell Riley as Enkidu and Jeremy Kleeman as Gilgamesh (photograph by Daniel Boud)

Clare Monagle

My cultural highlight of 2024 was seeing Pier Paolo Pasolini’s film The Hawks and the Sparrows at the Art Gallery of New South Wales. From 1966, it is a dazzling and weird meditation on Italy’s rapid industrial and commercial transformation in the postwar era, much of it narrated by a Marxist talking crow who offers parables from the past drawn from the Franciscan tradition. It stars Toto, the beloved clown of Italian cinema, who mugs and gestures with vaudevillian panache. In the middle are four minutes of extraordinarily moving footage of the funeral of Palmiro Togliatti. Half a million Romans lined the streets to farewell the communist leader in 1964, and the camera gazes respectfully on their mourning faces. The footage of the funeral procession is accompanied by a plaintive score by Ennio Morricone. Then we go back to talking crows and picaresque adventures. I still don’t know what to make of it, but I loved the film to my marrow and I’m so grateful to the AGNSW for tracking down a beautiful print and showing it on such a big screen.

The Hawks and the Sparrows, 1966

The Hawks and the Sparrows, 1966

Malcolm Gillies

This was Simone Young’s year. They say that conductors tend to eternity, while the rest of us plod towards extinction. At sixty-three, Young’s stature is ever-rising – at home and abroad – with new triumphs for her interpretations of Schoenberg, Bruckner, Mahler, and Wagner masterworks. Her reputation for reeling in the really big, sometimes problematic, fish of classical repertory has been further consolidated, whether with Gurrelieder (ABR Arts, 3/24), the craggiest symphonic juggernauts, or her distinctive re-readings of The Ring operas. Under her artistic leadership, the Sydney Symphony Orchestra is approaching high noon. Meanwhile, at the other end of the Hume Highway, its erstwhile rival continues to lick self-inflicted wounds, deflecting attention from the many virtues of Jaime Martín’s Beethoven Festival (ABR Arts, 11/24).

Simone Young conducts Gurrelieder (courtesy of Sydney Symphony Orchestra photograph by Dan Boud)

Simone Young conducts Gurrelieder (courtesy of Sydney Symphony Orchestra photograph by Dan Boud)

Georgina Arnott

In Ali Smith’s new dystopian novel Gliff, the future has no theatre. In 2024, we had My Brilliant Career (Melbourne Theatre Company). Funny, smart, singing, and dancing, Miles Franklin’s 1901 novel arrives on the stage different but recognisable in a moment thirsty for optimism. Kala Gare’s Sybylla, her Broadway smile, nestles into the character’s contradictions and captures Franklin’s hope for her ‘fellow Australians’. A Midsummer’s Night Dream (Bell Shakespeare) was tender and polished, my highlight from a season of thoughtful and riveting Bell productions. LaToya Ruby Frazier’s Monuments of Solidarity (Museum of Modern Art, New York) blended photography, biography, and performance – the despair in neglected Pennsylvanian towns rendered ripe, heavy, and intricately networked down generations and across communities. Bangarra’s architectural Horizon choreographed the human form into complex, extraordinary shapes to tell Indigenous stories from the Pacific Ocean – an immersive performance outside language’s limits.

Richard Pyros and Ella Prince (photograph by Brett Boardman)

Richard Pyros and Ella Prince (photograph by Brett Boardman)

Peter Tregear

My highlights for this year also operatically bookended it. Victorian Opera’s production of Candide in February (ABR Arts 2/24) surely banished any lingering doubt some may still have as to whether Bernstein’s foray into more operatic territory really works (it does!). Director Dean Bryant and designer Dann Barber, alongside a knock-out cast (including Katherine Allen in ‘glittering’ form as Cunégonde), pulled off a theatrical triumph that is deservedly being re-staged by Opera Australia in Sydney early next year. I thought I would never experience a finer production of Handel’s Giulio Cesare in Egitto (1724) than David McVicar’s fabled 2005 production for Glyndebourne. Angel Place is no opera house, but Pinchgut nevertheless approached it for sheer all-round quality (ABR Arts, 11/24). Standout performances from countertenors Tim Mead (Caesar) and Hugh Cutting (Tolomeo), alongside fast-rising Australia soprano Samantha Clarke (Cleopatra), were matched by superb music direction and direction from Erin Helyard and Neil Armfield respectively, alongside a clever, efficient design by Dale Ferguson.

Euan Fistrovic Doidge as Maximilian and Katherine Allen as Cunégonde (photograph by Charlie Kinross)

Euan Fistrovic Doidge as Maximilian and Katherine Allen as Cunégonde (photograph by Charlie Kinross)

Jordan Prosser

The long tail of 2023’s Hollywood strikes left this year’s release calendar looking unusually thin; all the more room for some genuinely unexpected independent and international fare. Mohammad Rasoulof’s The Seed of the Sacred Fig was the year’s best thriller, starting out as family drama and ending as pure social horror, a blistering indictment of contemporary Iranian culture. Elsewhere, a double bill of films about doubles grappled with our growing cultural appetite for bodily modification: Aaron Schimberg’s A Different Man, with Sebastian Stan and Adam Pearson as dueling off-Broadway actors (ABR Arts, 10/24), and Coralie Fargeat’s The Substance, starring Demi Moore and Margaret Qualley as competing aspects of a fading starlet’s ego (ABR Arts, 9/24). But 2024’s most purely entertaining outing was Edward Berger’s Conclave, featuring Ralph Fiennes and Stanley Tucci among an ensemble of devious cardinals gossiping, quarrelling, and vaping their way through the high-stakes process of electing a new pope (ABR Arts, 11/24).

Prosser Ralph Fiennes in Conclave (British Film Festival)

Prosser Ralph Fiennes in Conclave (British Film Festival)

Andrew Fuhrmann

Back in late 2022, choreographer Sandra Parker was selected as part of the inaugural Australian Ballet residency. The fruit of that experience is the extraordinary Safehold, which premièred in November at Melbourne’s ETU Ballroom. Performed by Anika de Ruyter, Rachel Mackie, and Oliver Savariego, it is rigorous, formal, austere, and high concept, tackling questions of social cohesion and individual expression. It is also the most engrossing and troubling piece of contemporary dance I have seen in ages. Indeed, I have become obsessed with the secrets of its subtle variations, its allusive gestures, its patterned ambiguities. There is a dim glow of revelation in this work, some hint of the oracular. The choreography is complemented by an otherworldly soundscape by composer Lawrence Harvey. Other 2024 dance highlights include Ghenoa Gela’s beautifully melancholy Gurr Era Op, Lucy Guerin’s new duet One Single Action, and the carnival of colour that is Dancenorth’s Wayfinder.

Oliver Savariego, Anika de Ruyter, and Rachel Mackie in Safehold (photograph by Gregory Lorenzutti)

Oliver Savariego, Anika de Ruyter, and Rachel Mackie in Safehold (photograph by Gregory Lorenzutti)

Ben Brooker

Helen Garner once wrote that live performance either gives the audience energy or saps them of it, an observation all the more true for sleep-deprived parents of toddlers like me. This year, I didn’t see much theatre by my standards, but two works reminded me of text-based theatre’s ability to vitalise the heart, soul, and mind. At fortyfivedownstairs was Benjamin Nichol’s superb double bill, Milk and Blood, about a socially alienated single mother and male sex worker, respectively (ABR Arts, 8/24). Tight storytelling, committed performances, and adroit direction alchemised into two compelling hours of theatre. Everyone in Melbourne, it seems, was astonished by Sarah Goodes’s trad revival of Edward Albee’s classic Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?. I saw it at Red Stitch when it was already dazzling (ABR Arts, 11/23), and hear it lost nothing on transferring to the much larger Comedy Theatre. Next stop: Sydney.

Charles Purcell as Daddy in Blood (photograph by Sarah Walker)

Charles Purcell as Daddy in Blood (photograph by Sarah Walker)

Michael Shmith

It was as heartening as it was enlightening to see Victorian Opera’s two very different productions. The first, La rondine, was a tribute to the centenary of Puccini’s death; the other, the première of Jonathan Mills’s long-awaited Eucalyptus. Both operas, well staged and finely performed, were presented in the cavernous Palais Theatre, a makeshift operatic venue that makes me positively long for the reopening of the State Theatre. Elsewhere, at the Athenaeum, Melbourne Opera heralded its Puccini celebrations with a vivacious new production of La bohème that underlined how this increasingly adventurous company, which receives no public funding, can best the so-called national company at almost every turn. As part of its desultory Melbourne season, Opera Australia’s Tosca – originally staged, to great success, by Opera North, in England – was marooned in the middle of the Margaret Court Arena, and suffered accordingly. I felt acutely sorry for all concerned, especially the unseen orchestra and the valiant cast.

Leave a comment

If you are an ABR subscriber, you will need to sign in to post a comment.

If you have forgotten your sign in details, or if you receive an error message when trying to submit your comment, please email your comment (and the name of the article to which it relates) to ABR Comments. We will review your comment and, subject to approval, we will post it under your name.

Please note that all comments must be approved by ABR and comply with our Terms & Conditions.