Visual Arts

As the author of Rock Chicks: The hottest female rockers from the 1960s to now (2011), I was excited to plunge back into the world of rock and roll to review the Linda McCartney retrospective that is currently showing at the Art Gallery of Ballarat. I’ve also written about Paul McCartney and John Lennon, so am quite familiar with these lads from Liverpool.

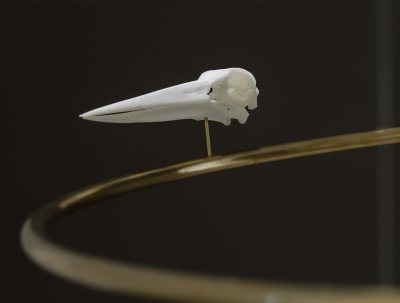

... (read more)This splendid exhibition is named for Doug Aitken’s three-channel video NEW ERA (2018), which revisits Martin Cooper, the elderly American inventor of the mobile telephone and his first call on the device in 1973. The video is set in a mirrored hexagonal room at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Sydney, its multiplying reflections fracturing and confounding place and time, wrapping around visitors. The work neatly encapsulates American artist Doug Aitken’s interests: how do humans and their technologies sit in the natural world? Importantly, how do we use these technologies to see the world we live in, to make it meaningful? The idea recurs throughout Aitken’s art and writings; it is manifested in the mirrors that incorporate us in his works.

... (read more)French Impressionism from the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

Given that the NGV has postponed Melbourne Winter Masterpieces 2020: Pierre Bonnard until 2023 due to the pandemic, and that international borders will remain closed for the foreseeable future, it is a relief that this major exhibition has gone ahead, notwithstanding a month-long delay because of the latest lockdown. We are indeed fortunate to see Impressionist works from a renowned international museum like Boston’s Museum of Fine Arts. French Impressionism, an exhibition of more than one hundred works, features Monet, Renoir, Pissarro, Cassatt, Sisley, Morisot, and Caillebotte. It includes seventy-nine works never before shown in Australia.

... (read more)Hilma af Klint: The Secret Paintings

Hilma af Klint: The Secret Paintings is attracting steady crowds at the Art Gallery of New South Wales (AGNSW). Perhaps enthusiasm is too ebullient a word for the pervading mood of reverence, but clearly Hilma af Klint’s newly minted reputation preceded her. The humming scrutiny is silenced in the famous double-height space in Andrew Anderson’s 1972 building: ten enormous abstract paintings, each more than three metres high, surround viewers in an installation not unlike the temple that the artist originally planned for them. Remarkably, The Ten Largest were painted in 1907, part of The Paintings for the Temple project between 1906 and 1915 that eventually comprised 193 paintings. This ambition and scale were not seen anywhere else at that time: the phenomenon that is af Klint is rewriting the history of modern art.

... (read more)Ever since experiencing my first séance at the Victorian Spiritualist Union in the mid-1960s, when I made contact with my godmother and uncle, I have been fascinated by the supernatural. Over the years, I have visited fortune-tellers, astrologists, clairvoyants, and others claiming to have psychic powers. For the most part, these have proved a lot of generalised mumbo jumbo, but a few claims have been remarkably accurate. In 1989, I was amazed when a London clairvoyant told me she had a message from Father: ‘I’m sorry for the way I treated your mother and left the family, but now she’s married to another very difficult man.’ How could she have invented this?

... (read more)Given the subject matter and ethos of the 2021 TarraWarra Biennial Slow Moving Waters, it is fair to assume that it was conceived as an immediate response to the period we have just endured and the global, national, and local impact of the pandemic. Yet it was initially scheduled to open in 2020 and delayed because of Covid-19 and Melbourne’s two extended lockdowns.

... (read more)Non-linear, interactive, random: hypertext fiction has scrambled our expectations of what narrative can be and how it can work. Today, control is wrested from authors, weth readers using hyperlinks to navigate their own trajectory through multiple possible stories experienced in the virtual spaces of the internet. But what happens when those unpredictable pathways unfold across a physical space, negotiated through an ambulatory encounter in an actual, material environment rather than a click of the fingers.

... (read more)I have frequented too often the gift shops of Australian Impressionism. Back in 1985, I mooned over David Davies’ Templestowe twilight scene before purchasing the corresponding tea towel (for my mum), Fire’s On placemats with matching coasters (for my dad), and lost child mugs (for my siblings, only one of whom took offence).

... (read more)The National 2021: New Australian Art, conceived in 2017, is a biennial survey exhibition to ‘address the specificities and nuances of what it means to make art from and for an Australian context at this point in time’. It is a joint initiative of the Art Gallery of New South Wales (AGNSW), Carriageworks, and the Museum of Contemporary Art, Australia (MCA). In its first iteration, the ethos of collaboration – not just between these three major Sydney art institutions but between curators, artists, and writers – was writ large.

... (read more)The works of New York artist Gregory Uzelac are currently being exhibited behind a set of nondescript, graffiti-laden doors on Sydney’s Bourke Street. The exhibition, titled Nice Is Different Than Good, has an underground feel to it. The art is presented on tarpaulin and pizza boxes, alongside traditional canvas. In each piece, neon-hued paint has been splashed about in shapes that are abstract, confronting, and occasionally reminiscent of Wassily Kandinsky.

... (read more)