Fiction

The death of the white male novelist, lately the subject of a fistful of literary think-pieces, has been greatly exaggerated. Yet it is a truth widely acknowledged that such authors now lack much of the cultural cachet that they once brazenly wielded. The challenge for these writers has been to transmute themselves into narrative subjects more palatable to the sensibilities of a shifting readership. Some continue to doggedly write self-adjacent fictions; others have willed a kind of metamorphosis, their subjectivities transposed or otherwise suppressed. Then there are those that try to do both. In the case of Rhett Davis’s Arborescence, this results in a novel with a striking elevator pitch: it is about people turning into trees.

... (read more)On the Calculation of Volume: Book I by Solvej Balle, translated from Danish by Barbara J. Haveland & On the Calculation of Volume: Book II by Solvej Balle, translated from Danish by Barbara J. Haveland

In a famous thought experiment based on the notion of ‘eternal return’, German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche asked what it would be like to live the same life over and over again, for eternity. Nietzsche’s intention was to set a kind of test that encourages us to consider whether we are living our best life, the life that makes us happiest.

... (read more)Who should we celebrate, or perhaps fault, for the publishing success of books labelled ‘outback noir’ in Australia over the past decade? Our starting point could be Jane Harper’s bestselling book The Dry (2016). The cornerstone of the genre for the author of The Leap, Paul Daley, is the seminal Kenneth Cook novel, Wake in Fright, first published in 1961. The longevity of the novel owes much to the 1971 feature film of the same name, directed by Ted Kotcheff, remembered for the infamous filming of a visceral Kangaroo shoot and the actor Donald Pleasence playing a most unpleasant lech. The Wolf Creek film franchise also deserves an honourable mention, along with its larrikin psychopathic killer, Mick Taylor, if not the real-life mass murderer, Ivan Milat himself.

... (read more)In The Möbius Book, an ingenious merging of fact and fiction by American writer Catherine Lacey, Lacey recalls including in one of her pieces of short fiction a poem about growing up with ‘an angry man in your house … and if one day you find that there is / no angry man in your house – / well, you will go find one and invite him in!’ (The poem appears in Lacey’s stinging short story ‘Cut’, first published in The New Yorker in 2019.)

... (read more)Omar Musa’s first novel, Here Come the Dogs (2014), is a rousing dramatisation of the combustible sense of displacement and dissatisfaction simmering at the underrepresented margins of Australian life. Its protagonists are singular and compelling: each is tender and violent, hopeful and despairing, pitiful and triumphant. They all possess a uniquely hybrid identity, and each is searching for something that is always out of reach.

... (read more)What does it mean to have a past you are estranged from? In Australian-Croatian author Marija Peričić’s third novel, Foreign Country, the title recalls the familiar L.P. Hartley line, ‘the past is a foreign country’, and stretches its metaphorical coverage to include the terrain of grief, childhood, the dislocation of immigrating, and even the afterlife.

... (read more)An irony of this age, when everyone is connected to everyone else, is that loneliness proliferates. Martin Luther’s claim that a lonely man ‘always deduces one thing from the other and thinks everything to the worst’ is exemplified by the miserable spiralling of fervidly online isolates. This is the world of Tony Tulathimutte’s Rejection.

... (read more)For earlier generations, joining a cult typically signified a rejection of mainstream values – careerism, property ownership, the nuclear family – in favour of spirituality and communal living. Ata time when a mortgage and stable employment are no longer assumed to be within reach of an average thirtysomething in Australia, the workplace arguably becomes a cult, with its own perplexing lingo, rigorous standards for membership, and redefinitions of family.

... (read more)In an instance of delicious wit, a new South Australian publisher is called Pink Shorts Press. That Pink Shorts Press has chosen a satirical collection as one of its first titles represents an almost perfect alliance. The only potential fly in this unctuous ointment is the question resounding across the world at the moment: how, as an author, does one challenge reality, distort the facts, and subvert the narrative, when currently one person dominates most of the work traditionally ascribed to satirical creatives?

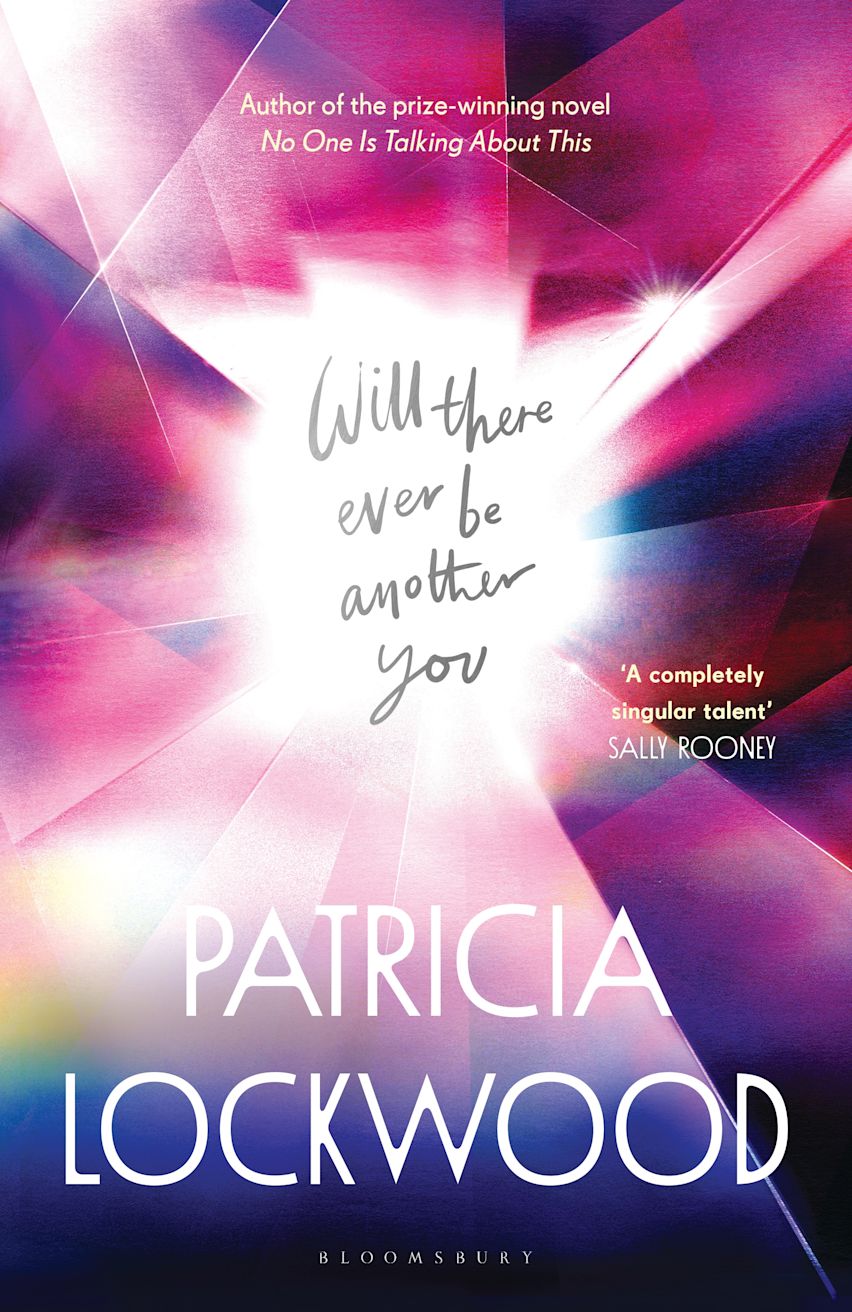

... (read more)Will There Ever Be Another You is a fever dream of a novel. That is, for much of the novel, the narrator is feverish with Covid-19. Our protagonist, never named, catches it in the first months of the virus’s epic global travels. It seems to have nabbed her on a family trip in early 2020, a journey undertaken after the death of her infant niece. Lockwood’s previous novel, No One Is Talking About This (2021), told the story of how the child’s life and death had propelled the protagonist out of her life in the ‘portal’ into the fleshed world of birth, illness, and love. Lockwood’s ‘portal’ is her designation for the internet, and the first half of No One Is Talking About This conveyed the rich shallowness of online life.

... (read more)