Language

The Australian summer was once again a story of Covid. Just as things were slowly reaching a state of ‘Covid-normal’, Omicron came along to present us with new, decidedly unwelcome, challenges. Despite Omicron, our summer did not pass by without one of its most defining features: sport. Many events went ahead as planned, not least the Australian Open tennis tournament.

... (read more)It was, inevitably, in a Zoom meeting that I first noticed the phrase. A colleague, excusing some minor oversight, explained it away with the words: ‘Sorry, Covid brain fog.’ Although I hadn’t consciously registered the expression before, I knew exactly what she meant.

... (read more)More than a year ago, I wrote about how those of us interested in language were tracking the many words and expressions being generated by the Covid-19 pandemic. At the time, all of Australia was in iso, and we had all turned to the joys (for some of us) of isobaking or learning to crochet. As the pandemic has dragged on, the language generated by it has changed. The Covidspeak of 2021 reflects our concerns about vaccinations, borders, and the impact of the Delta variant (often shortened to Delta or the Delta). The language of the pandemic has shifted to reflect our increasing frustration with slow vaccination rates, multiple and extended lockdowns and border closures, and government decisions and actions taken around these things.

... (read more)An email arrived in my inbox recently with an article from the British newspaper The Times. It was an obituary of John Richards, a former journalist and the man who founded the Apostrophe Protection Society in 2001. This organisation was dedicated to the protection of the apostrophe, ‘a threatened species’, according to Richards. He closed the Society down in 2019; aside from his age at the time (ninety-six), he concluded that ‘the ignorance and laziness present in modern times has won’.

... (read more)A little over a year ago, I was writing about the effects of the Black Summer of bushfires on our language. When Covid-19 hit, suddenly we were collecting the words of the pandemic. Despite the overwhelming focus on the pandemic (and its language) over the past year, the language of climate change has continued to evolve. My column on the Black Summer bushfires touched on the broader vocabulary of climate change and talked about both the language of climate crisis, such as tipping point, mass extinction, and eco-anxiety, and that of climate activism, such as school strikes, climate justice, and climate protests. More recently, however, it has struck me that the language around climate change is also increasingly that of climate grief.

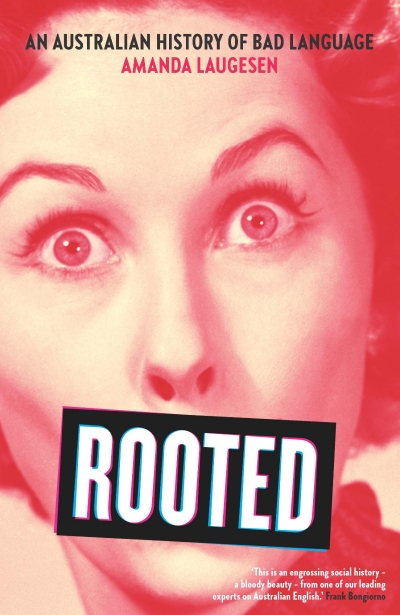

... (read more)Rooted: An Australian history of bad language by Amanda Laugesen

Amanda Laugesen, historian and lexicographer, is director of the Australian National Dictionary Centre at the ANU. In her latest book, the evocatively titled Rooted, Amanda considers the bountiful history of bad language in Australia. Her column in the December issue of ABR is devoted to the quaint old euphemism. Amanda talks about the inventive ways in which writers and editors have tried to placate the censor while also celebrating profanity.

... (read more)Australian English: The language of a new society edited by Peter Collins And David Blair

Disguising the words we dare not print has a long and fascinating history. From the late eighteenth century in particular, it became common in printed works to disguise words such as profanities and curses – from the use of typographical substitutes such as asterisks to the replacement of a swear word with a euphemism. When I was researching my recent book, Rooted, on the history of bad language in Australia, I was struck by the creative ways in which writers, editors, and typesetters, especially through the late nineteenth century and well into the twentieth, sought to evade censors and allude to profanity.

... (read more)