Travel

A few weeks ago, I went to see a painting in Branford, Connecticut. The owners live in a large house surrounded by woods. The picture is a fine copy of an early seventeenth-century portrait by Anthony Van Dyck. From my precarious vantage point on top of a wobbly stepladder, the canvas appeared to be machine-woven, which means that it cannot have been made, or paint applied to it, before the 1820s. Fortunately, the owners already know this, and are philosophical.

... (read more)Bamboo Palace: Discovering the lost dynasty of Laos by Christopher Kremmer

I first met a refugee from Laos, a teacher in her former life, while working part-time in a miserable egg-packing factory in the early 1980s. I had only a hazy notion of what had brought Ping to this country. Christopher Kremmer’s Bamboo Palace has now clarified those circumstances, and what a sad and painfully human story it is: of a 600-year-old socially iniquitous, politically benign kingdom destroyed and replaced by a totalitarian state.

... (read more)The collapse of the Soviet Union had one quite unexpected effect on world tourism – it opened up Antarctica. Cash-strapped, post-Communist Russia could no longer afford its large collection of Antarctic bases, or the fleet of polar-equipped vessels that supplied them. Many of these ships are now chartered out to adventure travel companies. As a result, the opportunities to visit Antarctica have increased dramatically, while the cost of getting down to the ice has dropped steeply. The Antarctic visitor total is now around 15,000 tourists a year, quite apart from the personnel travelling south to the forty-odd scientific bases.

... (read more)Into the Blue: Boldly going where Captain Cook has gone before by Tony Horwitz

This is a tale of a farm boy who grew up in ‘the world of the rural poor, [which] remained what it had been for generations; a day’s walk in radius, a tight, well-trodden loop between home, field, church, and, finally, a crowded family grave plot’. It is the story of James Cook’s dramatic escape from that loop, told by another equally restless soul, American journalist Tony Horwitz, who spent eighteenth months travelling the Pacific in the wake of Cook’s three great voyages of discovery.

... (read more)Aboriginal Australia & the Torres Strait Islands: Guide to Indigenous Australia by Sarina Singh

Last year, escaping the Olympics in Europe, I was amazed at the media coverage overseas, which always included Australian Indigenous motifs, art, dance and music. It seemed that, beyond Australia, its Indigenous people have a prominence and clout never realised at home. I hope that, in addition to the earnest German and Japanese backpackers who might use it, many Australians will read and employ this bargain of a book to discover some of the cultural wealth it encompasses.

... (read more)Roger McDonald seems never to do things twice in the same way. To be solemn about it, he has a mind which is both capacious and vivacious: events, experiences, things at large flood in to stock its territory, and become the livelier from their environment. Refreshed himself by Australia, he refreshes some of it in return.

The Tree in Changing Light is a case in point. This is a meditative work whose attention moves easily from the world’s physicalities and fluctuations to the appraising mind itself and back again. It is fluently, but not trivially, dialectical – an example of well-schooled attention which is itself a kind of schooling. Here, for instance, is an early passage:

... (read more)Aged twenty-two, I set out for Mexico, with, like Rousseau in Italy, a ‘heart full of young desires, alluring hopes and brilliant prospects’. I was determined to leave the confines of the sleepy metropolis that is Canberra, much as Isabella Bird, though infinitely more adventurous and literate, desired to escape her cloistered Victorian world. This ‘inner compulsion’, as Robyn Davidson describes it in her introduction to The Picador Book of Journeys (something her own books attest to powerfully), is a factor which gives travelogues ‘the power to reconnect us with the essential’. And if, by essential, one means illuminating the human condition in the way that any literature worth the name achieves, Davidson’s anthology gives us a sizeable sample.

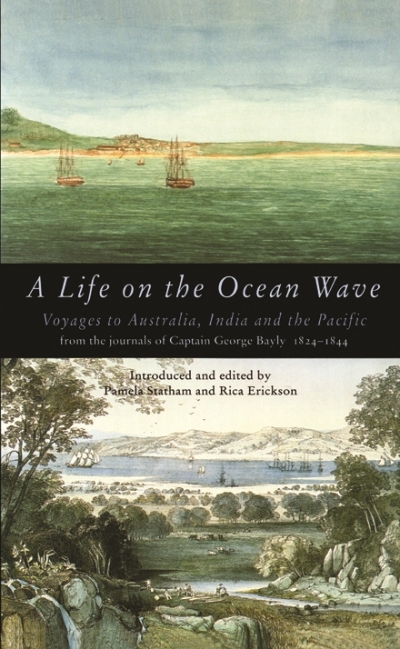

... (read more)A Life on the Ocean Wave: Voyages to Australia, India and the Pacific from the journals of Captain George Bayly 1824–1844 edited by Pamela Statham and Rica Erickson

A white-haired, white-bearded Captain George Bayly peers benignly out at us from the 1885 photograph frontispiece of A Life on the Ocean Wave. With epaulettes to his black uniform jacket, braided sleeves, a sword at his side and a ceremonial captain’s head-piece on the table beside him, Bayly looks the quintessential retired man of the sea. He looks like a man Charles Dickens should have been describing. We should be meeting him in some sea-side parlour, in some sailortown tea-palace. He looks as if he has a story to tell.

... (read more)As John Sligo spent thirteen years in Rome up to 1982, he experienced vita when life was still dolce in Hollywood-by-the-Tiber where he was one of those expatriates who hobnobbed with both exiled royal families and political refugees. Now a Sydney resident and prize-winning novelist, Sligo worked in Rome for the United Nations’ Food and Agriculture Organisation and also taught in English-language schools, but these tales mainly show him as a bon vivant, not only in the Italian capital but on excursions to Greece and India.

... (read more)After twenty-five years of political exile, Doris Lessing returns to her homeland – once Southern Rhodesia, now Zimbabwe – following the 1980 Marxist revolution. African Laughter documents four visits spanning the first decade of black majority rule, providing an intimate view of the birth, progress, and growing pains of a comparatively successful modern African nation. African Laughter also chronicles Lessing’s personal journey, a search for the landmarks of her memories.

... (read more)