Non Fiction

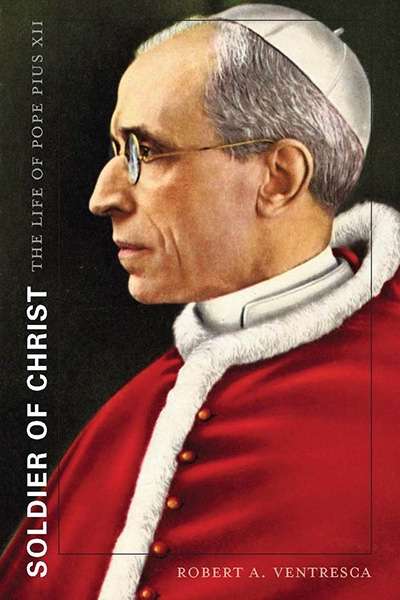

Soldier of Christ: The Life of Pope Pius XII by Robert A. Ventresca

Not the least portent of change in the Catholic Church since the Argentine Jesuit Jorge Bergoglio was elected as Pope Francis earlier this year has been mounting speculation that the new pontiff will disclose all documents in the Vatican archives concerning the most controversial of his twentieth-century predecessors, Eugenio Pacelli, who reigned as Pius XII from 1939 to 1958.

... (read more)The Last Blank Spaces: Exploring Africa and Australia by Dane Kennedy

Dane Kennedy reminds us that not so long ago exploring held an honoured place among recognised professions. Today, though, the job is extinct. For about a century and a half, the business of exploration was most vigorously pursued in Africa and Australia, yet among the thousands of volumes devoted to ...

... (read more)There are some poets whose works only seem to come alive when seen in the light of their other poems. Andrew Sant may well be one of these. A Sant poem, read on its own, can often seem thoughtful but rather lightweight; embedded in one of his books, given a context by the surrounding poems, it becomes animated by a set of consistent themes and obsessions.

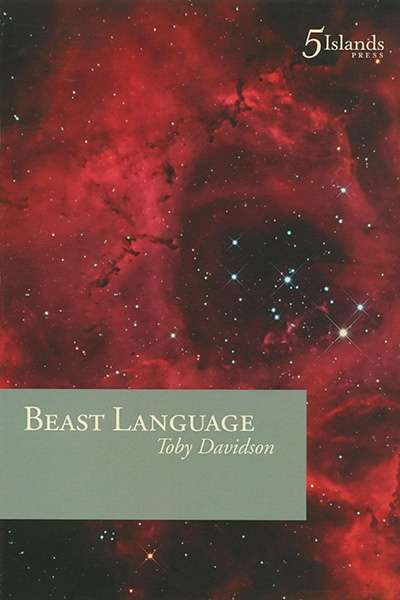

... (read more)‘Poetry is a long apprenticeship,’ says Toby Davidson at the start of his first collection. He is certainly a poet who has mastered far more than the basics. Beast Language is only seventy-seven pages long, but feels far more substantial. Davidson has travelled a long way: from west coast to east, from novice to scholar ...

... (read more)Confronting the Classics: Traditions, Adventures and Innovations by Mary Beard

When Confucius was asked by his disciples how they should become wise, he would enjoin them to study the classics; over two millennia later and much closer to home, Winckelmann declared that it was only by imitating the supreme masterpieces of the Greeks that we too might one day become inimitable – putting his finger on the paradox that the greatest originality always has deep roots in the past.

... (read more)Taking Stock: The Humanities in Australia edited by Mark Finnane and Ian Donaldson

This is a highly intelligent collection of essays by some of the nation’s finest minds about the ebb and flow of intellectual endeavour in the humanities since the institution of the Australian Academy of the Humanities in 1969. In the thirty-one essays – built around keynotes, panels, and responses – there are too many gems among them for me to be willing to pick out individual contributions for particular attention. If you care for the life of the mind and for our culture, download the e-book and peruse it, according to your interests. These are mainly stories of success, in transforming disciplines and the like. Less flatteringly, they are also a reminder that the humanities were more central in Australian universities back in 1969 than now.

... (read more)From a Distant Shore: Australian Writers in Britain 1820–2012 by Bruce Bennett and Anne Pender

From the earliest days of white settlement, Australians have made the voyage to Britain. Many stayed for long periods and some forever. Prominent among the more permanent residents were writers, prominent not only in terms of numbers but also because it was they who in large part created the stories and legends of Australians abroad. Some left without regret, lambasting their local world as ‘suburban’, hostile to originality and creativity. But Australian writers were not only denizens of a small, narrow society. They also lived in an English-speaking imperial world constructed in terms of metropolises and provinces. Thus Australian writers went to Britain in search of better opportunities for publication, wider markets for their wares, and to become part of a critical mass of writers, critics, intellectuals in a more complex, variegated society. When nationalist fervour was strong, local attitudes to expatriates could be ambivalent if not hostile. In 1967 Christina Stead was named by the Britannica Australia Award for Literature Committee as ‘the outstanding novelist of this day’ but was not given the prize because it was noted that she had not lived in Australia for forty years and that her contribution to literature had little reference to Australia.

... (read more)Unlike Hawthorne: A Life (2003), Brenda Wineapple’s penetrating and engaging biography of Nathaniel Hawthorne, Hawthorne’s Habitations, is a work of literary criticism informed by a narrow but fascinating range of biographical details and sources. These details support Robert Milder’s construction of an author ‘divided’ by contradictory drives that remained unresolved in Hawthorne’s fiction and life.\

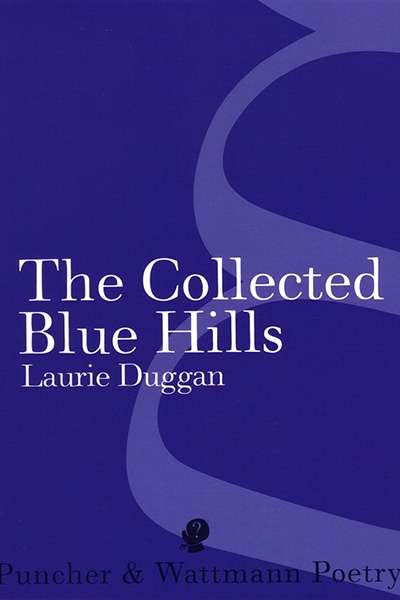

... (read more)In The Resistance to Poetry (2004), James Longenbach claims that ‘Distrust of poetry (its potential for inconsequence, its pretensions to consequence) is the stuff of poetry.’ The Australian poet Laurie Duggan has based a career on a creative distrust of poetry, or at least a certain kind of attitude to ...

... (read more)The Love-charm of Bombs: Restless Lives in the Second World War by Lara Feigel

My mother-in-law often spoke fondly of the Blitz. I had visions of her as a plucky young woman cycling down the bombed streets of London, going to work as a secretary to the stars of show business, enjoying ridiculously cheap hotel meals, and in the evenings going out on the town with an exciting boyfriend – perhaps a Turkish admiral, perhaps the man she later married. It always sounded as if she was having the time of her life. I was puzzled by this, because I knew her parents had both been killed in a bombing raid, though she didn’t talk about that. Was she unconsciously putting a positive spin on a time that must have been distressing and terrifying?

... (read more)