Non Fiction

American Notebook: A personal and political journey by Michael Gawenda

As the full extent of the American misadventure in Iraq becomes increasingly clear, liberal hawks, neo-conservatives and others who lent their voices to the initial call to arms have had cause to reconsider their positions. The rush to recant, however, has not exactly been a stampede. For the majority of its proponents, the decision to invade Iraq was so tied to an entrenched philosophy or ideology that to renounce the invasion would entail a more wide-reaching abandonment.

... (read more)Attempting to theorise or intellectualise rock‘n’roll, one could argue, is to miss the point. As Almost Famous’s egomaniac Stillwater vocalist Jeff Bebe put it, ‘I don’t think anyone can really explain rock‘n’roll – [except] maybe Pete Townsend’. In which case, Bebe would probably get a kick out of editor Theo Cateforis’s lovingly composed The Rock History Reader, which, unlike other publications in a similar vein, allows the theorising and intellectualising – the explaining – to nestle alongside autobiographical passages and personal anecdotes, providing a complex view of rock’s annals. If you didn’t already know who put the bomp in the bomp-a-bomp-a-bomp, you’ll probably find more than a few clues in this volume.

... (read more)God is Not Great: How religion poisons everything by Christopher Hitchens

The only salutary effect, it seems to me, of the evolution of religious fundamentalism over recent decades is the current reaction of some scientists, philosophers and public intellectuals. Since the end or the Enlightenment, interest in reasoned polemic against religion (which excludes communist attempts to extirpate it) has largely waned, possibly on the false supposition that the quarry had been mortally wounded. But the emergence of ruthless Islamist ambitions and terrorism, and the malign influence of elements of the Christian right and of right-wing Jewish groups, especially in George W. Bush’s America, appear at last to have spurred intellectuals to produce books and documentaries, to confer and to organise, to engage in resistance to what is rightly perceived as a religious assault on reason and liberal values, as the dying of secular light. The most prominent of the current critics are the philosophers Daniel Dennett and Michel Onfray, the biologist Richard Dawkins and the versatile Christopher Hitchens.

... (read more)East Timor’s former Prime Minister Mari Alkatiri has a knack of hiring international advisers who win access to his inner circle then publish tell-all books on leaving his employ. First there was Lynne Minion, whose Hello Missus: A Girl’s Own Guide to Foreign Affairs (2004) lampooned him mercilessly and sold like hot cakes. Now Paul Cleary follows the pattern, but in a more respectable book, worthy of serious attention.

... (read more)Lands of Shame: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander ‘Homelands’ in Transition by Helen Hughes

Helen Hughes was a professional development economist who worked at the World Bank from 1968 to 1983 and then, as an academic, headed the National Centre for Development Studies at the Australian National University from 1983 to 1993. Since then, she has been a senior fellow at a conservative think-tank, the Centre for Independent Studies, where she initially focused on issues of development in the Pacific and, since 2004, in remote indigenous Australia.

This book’s launch was timed to coincide with the fortieth anniversary of the 1967 referendum. Hughes sets out to assess and address the ‘Aboriginal problem’ for 90,000 indigenous people who live in some 1200 ‘homeland’ settlements established in remote Australia from the 1970s, according to Hughes. Her book focuses on the ‘homelands’, because, in her view, their occupants’ deprivation is the greatest.

... (read more)The official published accounts of Captain Cook’s three great voyages (1768-79) were immense popular successes in Britain. That for the third voyage sold out within three days of publication in 1784. When the Frenchman La Pérouse sailed from Botany Bay in March 1788 into the Pacific – and into oblivion – he remarked that Cook had done so much that he had left him nothing to do but admire his work. In the previous year, the German, Georg Forster, had published in Berlin his eulogy of Cook, Cook der Entdecker (Cook the Discoverer). Cook was the first international superstar, and time has only increased his celebrity status. Major scholarly biographies continue to be published, and seminars which feature Cook in their titles are sell-outs. The name is box-office magic.

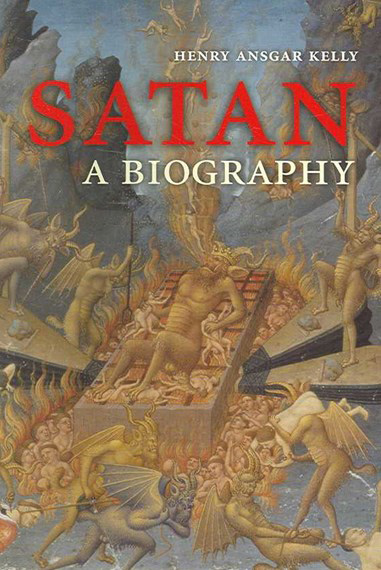

... (read more)One stock form of biography is attempting the rehabilitation or revision of a character whose reputation seems well settles. In theory, the most challenging of such projects is that of returning the Devil, otherwise known as Lucifer or Satan, from the lowest circle of human estimation to a more sympathetic or nuanced position. With a tip of the hat to Jack Miles’s God: A Biography (1995), Henry Ansgar Kelly constructs a diabolical life of sorts, retracing the idea of Satan across the centuries from ancient Israel to contemporary Catholicism. This is partly a popularising presentation of scholarly research on an idea and its variations, and partly the outworking of the attractive conceit, borrowed from Miles, that behind the pages of scriptural and apocryphal material lies the development of a real character.

... (read more)Which School?: Beyond public vs private by Joana Mendelssohn

Joanna Mendelssohn is best known as an art critic and historian. After the publication of an essay in The Griffith review entitled ‘Going Private’, Pluto Press commissioned her to write a piece for its Now Australia series. Similar to Black Inc.’s Quarterly Essays, but even more determinedly non-academic, the Pluto Press format is part of a publishing phenomenon and covers a range of political, intellectual and cultural views on public issues and debates. The authors are not necessarily experts in the area they write about, nor are their views always based on systematic, in-depth research.

... (read more)A little over a year ago, the contents of George W Bush’s iPod were made public. The revelation offered momentary respite to the beleaguered president as the international press seized upon the playlist, scrutinised its contents and, much to the relief of the White House, made tallies of song titles and popular music genres instead of the latest casualties in Iraq. IPod One, as it was dubbed, was shown to be heavy on country and western music and 1970s rock, and light on just about everything else. ‘No black artists, no gay artists, no world music, only one woman, no genre less than 25 years old, and no Beatles,’ reported the London Times.

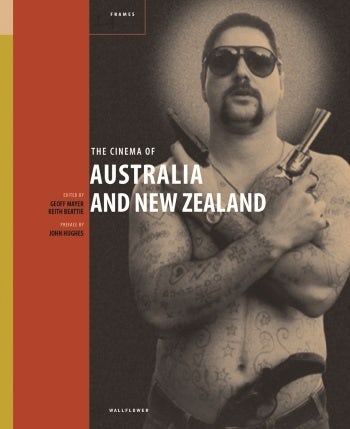

... (read more)The Cinema of Australia and New Zealand edited by Geoff Mayer and Keith Beattie

The Cinema of Australia and New Zealand is the thirteenth of Wallflower Press’s ‘24 frames’ series, but there is no need for the editors to feel superstitious on that account. This is a series which presents certain problems. It requires the editor(s) of each volume to choose twenty-four films that are, in some degree, representative of the titular country, or, as the case sometimes even more dauntingly is, of two titular countries – and I know whereof I speak. Having edited Wallflower’s The Cinema of Britain and Ireland (2005), I can sympathise with the difficulties involved in trying to achieve any sort of representativeness across not one but two film-making countries. And I might add resentfully that Canada gets a whole volume to itself. Canada!

... (read more)