Archive

In the thirty or so years that she has been publishing fiction, Thea Astley has mapped out a literary territory very clearly her own, a territory that is defined in the first place by regional geography.

... (read more)What is the relation between poet and critic? No, not a topic for yet another tedious and oppositional debate at a writers’ festival. Rather, a question about the nature of oppositions, and the possibility of disrupting, or even suspending them, in the varied and delicate acts of literary criticism. Let me frame my question even more precisely: who is the ‘Gwen Harwood’ to whom I refer when I write about the poetry of a women who in recent years has become increasingly public, celebrated and accessible?

... (read more)Gwen Harwood’s poetry has been the subject of an increasing number of essays and articles during the last decade; in the last twelve months three books have appeared (written by Alison Hoddinott, Elizabeth Lawson, and Jennifer Strauss) and a fourth (by Stephanie Trigg) is on the way. All of this industry, as well as the publication in the Oxford Poets series of a Collected Poems, is to be welcomed; few would deny that Gwen Harwood’s work deserves all the attention it gets, particularly as it continues to surprise and delight.

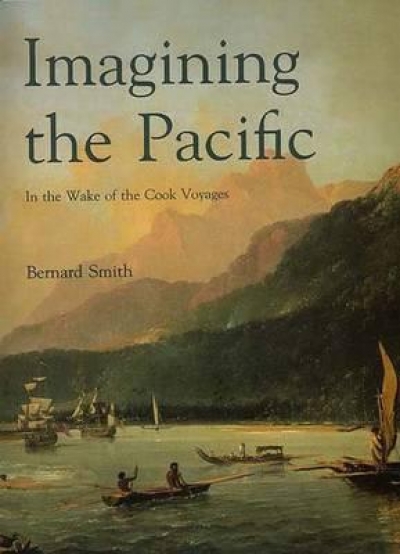

... (read more)Imagining the Pacific in the Wake of the Cook Voyages by Bernard Smith

Publishers are like invisible ink. Their imprint is in the mysterious appearance of books on shelves. This explains their obsession with crime novels.

To some authors they appear as good fairies, to others the Brothers Grimm. Publishers can be blamed for pages that fall out (Look ma, a self-exploding paperback!), for a book’s non-appearance at a country town called Ulmere. For appearing too early or too late for review. For a book being reviewed badly, and thus its non-appearance – in shops, newspapers and prized shortlistings.

As an author, it’s good therapy to blame someone and there’s nothing more cleansing than to blame a publisher. I know, because I’ve done it myself. A literary absolution feels good the whole day through.

... (read more)