History

Terminus: Westward expansion, China, and the end of the American empire by Stuart Rollo

What a difference a decade makes. When the second decade of the millennium opened, the United States was advocating an open door for trade and investment with China. In November 2011, President Barack Obama, in a speech to the Australian Parliament, revealed Washington’s new strategic and economic policy: the Pivot to Asia.

... (read more)The Empire of Climate: A history of an idea by David N. Livingstone

The birth seasons of the Democrat and Republican presidential candidates may be one of the few details of the nominees that have escaped close scrutiny in the lead-up to November’s election. Such a neo-Hippocratic political analy-sis might also consider their general body types, genealogies, dispositions, and partners, according to the approach of a 1943 study, Lincoln-Douglas: The weather as destiny. Written by a Chicago physician and professor of pathology and bacteriology, William F. Petersen, the meteorological biography of Abraham Lincoln and his political opponent Stephen Douglas sought to make the case for the causal climatic forces on the political trajectories of its protagonists. Lincoln’s success was apparently thanks to his slender physique and ‘better equilibrium with the environment’.

... (read more)People Power: How Australian referendums are lost and won by George Williams and David Hume

People have peculiar but passionate views about referendums. A large number swear that in 1974 and 1988 the people voted against referendums on the existence of local government. To them, local government is ‘unconstitutional’, so they don’t have to pay their council rates. Members of the same cohort also proclaim that they have a constitutional right to trial by jury for state criminal offences and a right to compensation on just terms if a state compulsorily acquires their land.

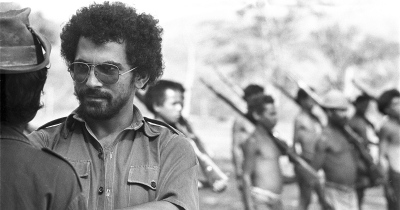

... (read more)Twenty-five years ago, an international peacekeeping force entered East Timor, delivered it from Indonesian occupation, and placed it under United Nations administration. Known as the International Force East Timor (InterFET), it had 11,000 troops from twenty-three countries and was commanded by an Australian major general. Everything about these events seemed miraculous. East Timor’s independence had long been regarded as impossible; a top adviser to President Franklin D. Roosevelt observed during World War II that it might eventually achieve self-government, but ‘it would certainly take a thousand years’. Indonesia invaded East Timor in 1975 while the latter was in the process of decolonising from Portugal, annexed it the following year, and declared its rule ‘irreversible’.

... (read more)Fact or Fission?: The truth about Australia's nuclear ambitions by Richard Broinowski

Richard Broinowski, a retired senior diplomat who has served in seven legations, three as ambassador, has long been interested in matters nuclear, as this excellent work demonstrates. Broinowski traces Australian nuclear developments from the early days of World War II to the most recent developments under Prime Minister John Howard. In the process, he chronicles Australian nuclear ambitions, from the early flirtations with acquiring a nuclear weapon and its related strike capability, to the later development of uranium exports.

... (read more)They Called It Peace: Worlds of imperial violence by Lauren Benton

The Australian War Memorial (AWM) is unique among the former settler Dominions in our reluctance to acknowledge as warfare violent conquest and dispossession of Indigenous peoples. The national war museums of Canada, New Zealand, and South Africa all contain exhibits dedicated to military conflicts between First Nations and European colonisers, yet the AWM has for decades refused to heed calls for a frontier war gallery at Mount Ainslie. As veteran journalist David Marr noted earlier this year, while the AWM saw fit a decade ago to memorialise explosive detection dogs and their handlers, ‘we haven’t yet found the space in those halls to commemorate the war that is the basis of our country’s existence’. Kim Beazley, appointed in 2023 to chair the Australian War Memorial Council, recently signalled a shift in direction and has promised that the AWM will soon ‘give the Aboriginal population the dignity of resistance’.

... (read more)Travelling to Tomorrow: The modern women who sparked Australia’s romance with America by Yves Rees

Yves Rees’s accessible, entertaining study blends personal experience with rich archival research into a group of disparate women who followed their passion from Australia to the United States at a time when it was relatively easy for a white woman with talent and a few connections to just show up in Hollywood or New York and get to work. They are very different women – a surfer, a dentist, a concert pianist, a nurse, a decorator, an artist, a lawyer, and a writer – all fiercely courageous trailblazers in their own way. Travelling to Tomorrow weaves their stories together in a loosely chronological shape, using deep research to ground Rees’s imagining of these women’s hopes, dreams, achievements, and disappointments.

... (read more)History in the House: Some remarkable dons and the teaching of politics, character and statecraft by Richard Davenport-Hines

In Yes, Prime Minister, Sir Humphrey Appleby spells out the really important things in British life: Radio 3, the countryside, the law, and the universities – both of them. It is an amusing reminder that writing on higher education in the United Kingdom focuses on just a handful of institutions. In History in the House, Richard Davenport-Hines takes this approach much further – to just one discipline in a single Oxford college, Christ Church, known as ‘the House’.

... (read more)The Eastern Front: A history of the first world war by Nick Lloyd

This is a massive book: 506 pages of text; eighty-nine pages of references and bibliography; seventeen maps, all of them full page or more; and forty-two illustrations. It is also an important book, and it is easy for the reader to follow Nick Lloyd’s argument. The Eastern Front is a major corrective to how most readers here and in the United Kingdom, France, and the United States understand the Great War, as it was once called.

... (read more)November 1942: An intimate history of the turning point of the Second World War by Peter Englund, translated from the Swedish by Peter Graves

As its title tells us, this book focuses on one month of World War II: November 1942. Swedish author and historian Peter Englund argues that this month was the turning point of the war. In North Africa, the Germans were on the retreat after the Allied victory at El Alamein. American forces began their land operations against the Axis powers by invading French Morocco and Algeria. In the Pacific war, the battle of Guadalcanal reached its decisive climax, while Australian troops recaptured Kokoda after pushing the Japanese back along the Kokoda Track. Most importantly, on the Eastern front, the Red Army launched an attack that surrounded the German 6th Army in Stalingrad. Two months later, the 91,000 German troops still alive in the ruins of the city surrendered. Almost all of them perished in captivity.

... (read more)