Indigenous Studies

The name of Yorta Yorta elder William Cooper shines bright in the history of Aboriginal activism in Australia between the two world wars. It is linked with the formation of the Australian Aborigines’ League, of which he was the founding secretary; the Day of Mourning on the anniversary of white settlement in 1938; and a petition intended for George V, signed by almost 2,000 Aboriginal people and demanding Aboriginal representation in parliament. This last was perhaps Cooper’s most cherished project. He spent years gathering signatures and waiting for the most opportune moment to present it; his disappointment at the indifferent response of the Australian government darkened his final years.

... (read more)The World Turned Inside Out: Settler colonialism as a political idea by Lorenzo Veracini

It is now well accepted that the invasion and colonisation of the Indigenous territories we call ‘Australia’ are emblematic of a particular type of colonialism. A settler colony, unlike, say, an extractive colony (where Indigenous peoples may be exploited in pursuit of resources but where permanent settlement does not necessarily follow), seeks to establish a new society on an acquired territory (regardless of the means by which that territory was acquired), intentionally displacing and eliminating the Indigenous inhabitants. In settler colonial societies, the settler came to stay.

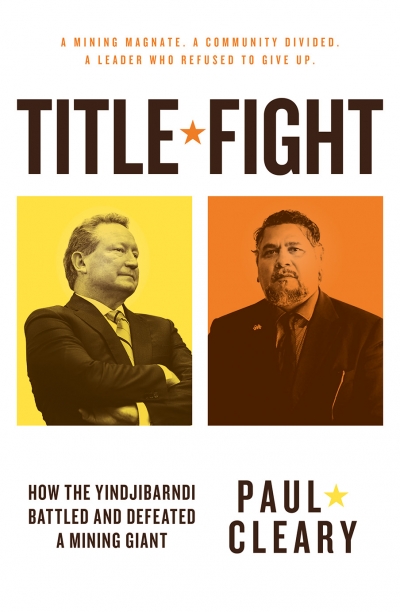

... (read more)Title Fight: How the Yindjibarndi battled and defeated a mining giant by Paul Cleary

On the wall of Yindjibarndi leader Michael Woodley’s modest office in the Pilbara Aboriginal community of Roebourne hangs a large framed portrait of Muhammad Ali and a pair of boxing gloves. It seems a highly appropriate metaphor for the tale of this small Aboriginal group’s thirteen-year resistance to one of Australia’s most powerful companies, now recounted by former Australian journalist Paul Cleary.

... (read more)True Tracks: Respecting Indigenous knowledge and culture by Terri Janke

This book hit a nerve. It’s not that Terri Janke sets out to confront her readers; if anything, she is at pains to convey goodwill. Janke, who is of Meriam and Wuthathi heritage, writes to build bridges and, above all, to give useful advice. But beneath this is a profound challenge for those who write and create: that is, to rethink how we know.

... (read more)Tongerlongeter: First Nations leader and Tasmanian war hero by Henry Reynolds and Nicholas Clements

Tongerlongeter was surely one of Australia’s toughest military leaders. Henry Reynolds and Nicholas Clements expressly narrate his story to affirm the place of the Frontier Wars in the Anzac pantheon. Reflexive conservative responses to such arguments – that Anzac Day commemorates only those who served in the Australian military – are flawed and outdated. The Tasmanian frontier is one of Australia’s best-documented cases of violent operations against Aboriginal people. In 1828, Governor George Arthur, unable to gain control over the ‘lamentable and protracted warfare’, issued a Demarcation Proclamation later enforced by the formation of Black Lines, military cordons stretching several hundred kilometres across southern and central Tasmania to secure the grasslands demanded by white settlers.

... (read more)Farmers or Hunter-gatherers?: The Dark Emu debate by Peter Sutton and Keryn Walshe

For anyone who has spent substantial time recording Aboriginal cultural traditions in remote areas of Australia with its most senior living knowledge holders, bestselling writer Bruce Pascoe’s view that Aboriginal people were agriculturalists has never rung true. Farmers or Hunter-gatherers? The Dark Emu Debate – co-authored by veteran Australian anthropologist Peter Sutton and archaeologist Keryn Walshe – has already been welcomed by Aboriginal academics Hannah McGlade and Victoria Grieve-Williams, who reject Dark Emu’s hypothesis that their ancestors were farmers (like Pascoe himself).

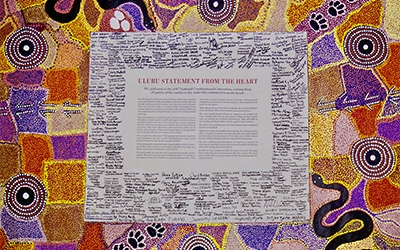

... (read more)Everything You Need to Know About the Uluru Statement from the Heart by Megan Davis and George Williams

The Uluru Statement from the Heart was made at a historic assembly of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples at Uluru in 2017. It addresses the fundamental question of how Indigenous peoples want to be recognised in the Australian Constitution. The answer given is a First Nations ‘Voice’ to Federal Parliament protected by the Constitution, and a subsequent process of agreement-making and truth-telling. This process should be overseen by a Makarrata Commission, from the Yolngu word meaning ‘the coming together after a struggle’. Inspired by the values enshrined in the Statement, Victoria has established such a process through the Yoo-rrook Justice Commission. ‘Yoo-rrook’ is a Wemba Wemba/Wamba Wamba word meaning ‘truth’.

... (read more)In early 2021, the Victorian government announced the creation of the Yoo-rrook Justice Commission to investigate the harms done to Aboriginal people through colonisation. Named after the word for truth in the Wemba Wemba/Wamba Wamba langauge, Yoo-rrook will be the first exercise of its kind in an Australian jurisdiction and one of the most significant responses yet offered to the call for Voice, Treaty and Truth issued by the Aboriginal peoples of Australia in the ‘Uluru Statement from the Heart’.

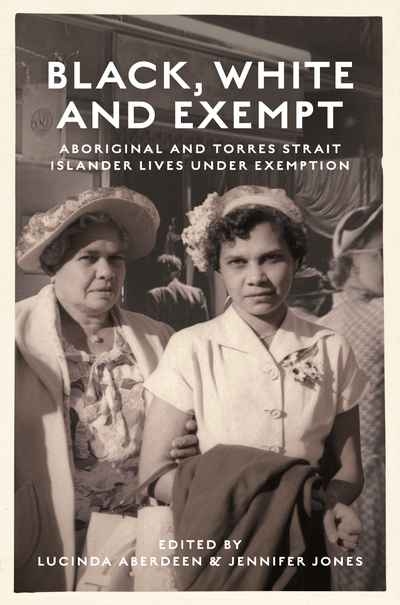

... (read more)Black, White and Exempt: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander lives under exemption edited by Lucinda Aberdeen and Jennifer Jones

In the process of British colonisation, Aboriginal people lost their country, kin, culture, and languages. They also lost their freedom. Governed after 1901 by different state and territory laws, Aboriginal peoples were subject to the direction of Chief Protectors and Protection Boards, and were told where they could live, travel, and seek employment, and whom they might marry. They were also subject to the forced removal of their children by state authorities. Exemption certificates promised family safety, dignity, a choice of work, a passport to travel, and freedom. Too often, in practice, exemption also meant enhanced surveillance, family breakup, and new forms of racial discrimination and social segregation.

... (read more)The Children’s Country: Creation of a Goolarabooloo future in north-west Australia by Stephen Muecke

In 1985, following the publication of their collaborative works Gularabulu: Stories from the West Kimberley and Reading the Country: Introduction to nomadology (with artist Krim Benterrak as co-author), Paddy Roe, possibly sensing that the young researcher would be of critical importance to his life’s project, suggested to Stephen Muecke that there needed to be a third book, The Children’s Country, about the rayi – the spirit children – and for human children to come. Muecke writes that he was unable to deliver the book at the time. Roe went on to establish the Lurujarri Heritage Trail following a songline along a ninety-kilometre stretch of coastline from Minyirr (Broome) to Minarriny (Coulomb Point).

... (read more)