Indigenous Studies

The nomenclature of indigenous policy is apt to mislead, casting indigenous people as the passive objects of progressively more enlightened régimes: protection, assimilation, self-determination. This view is resonant in the history propagated by Keith Windschuttle, among others. Contesting Assimilation sets out to debunk this historically inaccurate idea and the implicit condescension in the view that denies any role for indigenous people in shaping the policy environment. As the essays in this volume attest, the development of indigenous policy can only be understood as a product of the interaction of indigenous and non-indigenous reformers, engaged in a struggle of ideas as to how best to resolve the social issues occasioned by colonisation.

... (read more)Eye Contact: Photographing Indigenous Australians by Jane Lydon

There is a recuperative basis to Jane Lydon’s project that the measured tones of academic writing cannot disguise and that gives this book its energy. Lydon’s subject is the Coranderrk Aboriginal Station near Healesville, which was established in the 1860s in what Lydon describes as ‘consensual circumstances’. In the first decade of operation, the Aboriginal residents at Coranderrk achieved an un-characteristic and impressive degree of autonomy. Under the sympathetic management of John Green, there was, Lydon argues, ‘space for Aboriginal objectives and traditions to co-exist with newer practices’. As an early, initially successful expression of Aboriginal self-determination, Coranderrk has already attracted much scholarly attention, but Lydon takes a new tack, examining the extensive photographic archive created during the Station’s first forty years (it closed in 1924).

... (read more)A World of Relationships: Itineraries, dreams, and events in the Australian Western Desert by Sylvie Poirier

We use the term ‘The Dreaming’ to refer to an Aboriginal way of thinking about their place in the universe; it is ‘a cosmology, an ancestral order, and a mytho-ritual structure’, in the words of Canadian anthropologist Sylvie Poirier. The Western Desert people with whom she lived for many months in the 1980s and 1990s (the Kukatja – though she acknowledges the difficulties of such labels) call it tjukurrpa, a term whose meanings include ‘story’. The stories are about the world- and knowledge-creating ancestral creatures. In the Kukatja world, as manifested in the Western Australian communities of Wirramanu, Mulan and Yagga Yagga, the more prominent stories are about Luurn (kingfisher), Wati Kutjarra (two initiated men), Kanaputa (digging stick women), Marlu (kangaroo), Karnti (yam) and Warnayarra (rainbow snake). When Kukatja narrate the travels of these creatures, they select segments in the itinerary that account for the narrator him or herself as a person who belongs to the places named in the story.

... (read more)Eddie’s Country: Why did Eddie Murray die? by Simon Luckhurst

It is painful to read Eddie’s Country, a book that takes the reader beyond the formality, the statistics and the mind-numbing complexity of the Australian Royal Commission into Aboriginal Deaths in Custody held between 1987 and 1990. Instead, we are called to bear witness to the frustration and grief endured by one family as it sought answers to questions arising from the unexpected death, in police custody, of Eddie Murray.

... (read more)In 1993, when Victoria Haskins undertook research into the relationship between Aboriginal and white women, she was ‘plunged into the argument that white academics were only perpetuating colonialism by writing Aboriginal people’s history … that white Australians should not, could not, try to speak for Aboriginal people, nor try to represent the Aboriginal experience’. Left floundering by ‘the difficult politics of writing Aboriginal history as a white Australian scholar’, Haskins was unreceptive to her grandmother’s pleas to embark on the despised ‘trivial bourgeois pursuit’ of family history, dismissed as ‘middle-class … the province of mildly ridiculous ageing relatives, searching for the dates of their ancestors’ arrival in the colonies’. But curiosity about an old photograph of her grandmother as a fair-haired toddler with an Aboriginal nanny prompted her to root out her great-grandmother’s boxed papers, then languishing in an aunt’s garage.

... (read more)Telling the Truth About Aboriginal History by Bain Attwood

For the past twenty years, Bain Attwood has been trying to de-provincialise what he sees as an insular historiography of Aboriginal Australia by imploring colleagues to embrace the latest intellectual trends from France, America and New Zealand. In Telling the Truth about Aboriginal History, he expands on his many press articles on the ‘history wars’ and combines them with methodological reflection on postmodernism and post-colonialism. What advice does he have for his colleagues in the face of doubts cast on their work by newspaper columnists and other ‘history warriors’?

... (read more)Recognizing Aboriginal Title: The Mabo case and Indigenous resistance to English settler colonialism by Peter H. Russell

Peter Russell, a distinguished Canadian student of the politics of the judiciary, asks if ‘my people’ – the English settlers of Australia, Canada, New Zealand, and the US – can live honourably. Is their authority defensible against indigenous people’s charge that ‘my people’ bullied them out of their sovereignty? Because European colonial power has been shadowed by a sense of moral unease, interpreting the colonists’ laws matters. ‘There is a lot of leeway in the law,’ Russell observes, ‘and no more so than in legal cultures based on the common law.’ The High Court of Australia’s decisions in Mabo (1992) and Wik (1996) – making native title recognisable to the common law – seemed to Russell to confirm judges’ potential to be the conscience of liberal constitutionalism.

... (read more)Written in hotel rooms while working as a professional actor in various indigenous film, television and theatre productions, Peter Docker’s Someone Else’s Country is a deeply sensitive and at times intensely visceral engagement with contemporary indigenous culture. A work of non-fiction (the names are fictionalised), it is also a powerful historical document, which has at its heart the struggle of a non-indigenous author trying to find an authentic position from which to discuss the indigenous culture with which he largely identifies.

... (read more)Seeking Racial Justice by Jack Horner & Black and White Together by Sue Taffe

The Federal Council for the Advancement of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders (FCAATSI) was a national organisation that existed, in one form or another, from 1958 to 1978. For the main part, it drew its members from a network of both black and white groups, from active citizens and from those who wanted to be counted as such.

Two recent books examine the impact and legacy of this organisation. Black and White Together, by Sue Taffe, provides a detailed overview of the organisation from an historian’s perspective, while Seeking Racial Justice is an ‘insider’s memoir’, written by one of its non-indigenous members, Jack Horner. Both books tell this story in the context of the political shift from segregation to assimilation policies (1938–61), from assimilation to integration (1959–67), and from integration to self-determination (1968–78).

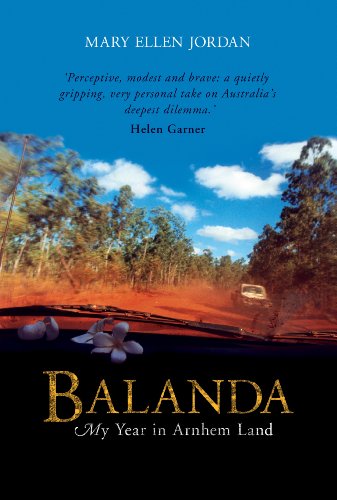

... (read more)The first time Mary Ellen Jordan’s name appeared in ABR (June 2001), it was followed by a brief, heated exchange. Bruce Pascoe responded to her ‘Letter from Maningrida’ mixing accusations of betrayal with a series of familiar analogies, in a stern warning that this kind of fearless journalism was not wanted. Melissa Mackey moved to Jordan’s defence. She had read courage, not fearless journalism, and, in open frustration, ended her reply by simply asking: ‘then what can we say?’ I read Balanda: My Year in Arnhem Land as part answer, part re-examination of that question.

... (read more)