Indigenous Studies

A striking black-and-white photograph on the front cover of Oodgeroo implacable and wise. And then the publisher’s blurb on the back cover

... (read more)The Encyclopedia of Aboriginal Australia edited by David Horton

The general editor introduces the Encyclopaedia of Aboriginal Australia with a number of challenging statements. He does not want it to be ‘just another encyclopaedia’. He has made it his policy, he writes, to have no ‘academic-style text references, linguists and other students of Aboriginal studies rarely appear, and there are no “studies suggest that” ... This encyclopaedia also aims to tum the usual convention on its head by presenting an Australia with no white people except as they impinge on Aboriginal society.’

... (read more)This is a sad, short book – sad in more ways than one. It is the last work of this century’s greatest authority on the Tasmanian Aborigines. It is the distillation of sixty years of detailed and diverse work. And it is deeply flawed.

Brian Plomley, who died earlier this year, was best known for his doorstop volumes on the original Tasmanians (The Friendly Mission and Weep in Silence). For these we owe Plomley a great debt. He dedicated decades of his life to getting inside the mind of G.A. Robinson, the so-called Conciliator of Tasmania’s last tribal Aborigines. His insights into that man and his era, and the thoroughness of his work on the thinly-spread evidence of pre-European Aboriginal culture in Tasmania, are unique. They would lead us to expect the present slim volume to be a rich distillation. Instead the undoubted riches are contaminated by errors both of fact and judgement.

... (read more)Textual Spaces: Aboriginality and cultural studies by Stephen Muecke

Stephen Muecke’s Textual Spaces offers both new material and versions of some of the essays he has published on Aboriginal and cultural studies published through the 1980s. Many of these have already been very influential, but the welcome appearance of the book invites consideration of the continuities in Muecke’s arguments, the programme they suggest.

... (read more)Ancestral Connections: Art and an Aboriginal system of knowledge by Howard Morphy

Morphy’s monograph is an instance of a problem in anthropological writing about Australian Aboriginal people, a problem of audiences. The public this book will reach (and please and enrich enormously) is international, made up of several thousand mostly Anglophone anthropologists students of art, particularly those researching or teaching about the contexts in which the art of non-Western peoples is created and first consumed. Yet the art of North East Arnhem Land (the Nhulunbuy/Yirrkala region) appeals to a much larger and more heterogeneous public than this. It is likely that Australians comprise a majority of this second public. Morphy, adviser to the Australian National Gallery in the later 1970s and early 1980s, can take some credit for that. And there is a third and even larger public still: those Australians who infrequently go to art galleries (they might spend a few hours in the ANG on a Canberra trip) but who are susceptible to a more informed perception of the subtlety, beauty and (most important) resilience of the classical heritage of Aboriginal culture.

... (read more)Mining and Indigenous Peoples in Australasia edited by J. Connell and R. Howitt & Aborigines and Diamond Mining edited by R.A. Dixon and M.C. Dillon

If John Hewson leads the next Australian government, we are likely to see a reversal of the current government ban on mining at Coronation Hill and the lifting of other impediments to mining. Should the fight to preserve an indigenous right to negotiate other’s access to mineralised lands have to be renewed, these two books will make invaluable background reading. They document the awesome political responsibilities on nation-states wishing to encourage economic development but trying also to satisfy the legitimate and changing claims of the traditional owners of mineralised lands. National leader’s political commitment to indigenous rights is only one of the issues highlighted here. Of equal importance is the complex and changing attitudes of the landowners themselves.

... (read more)Take this Child ...: From Kahlin Compound to the Retta Dixon Children’s Home by Barbara Cummings

Barbara Cummings’s history combines archival research, interviews with her peers, and autobiography to declare the common experiences of an Aboriginal sub-culture, the ex-inmates of the Retta Dixon Home in Darwin. She deems it ‘a first step in our healing process’. It is also an outstanding contribution to feminist and Aboriginal history.

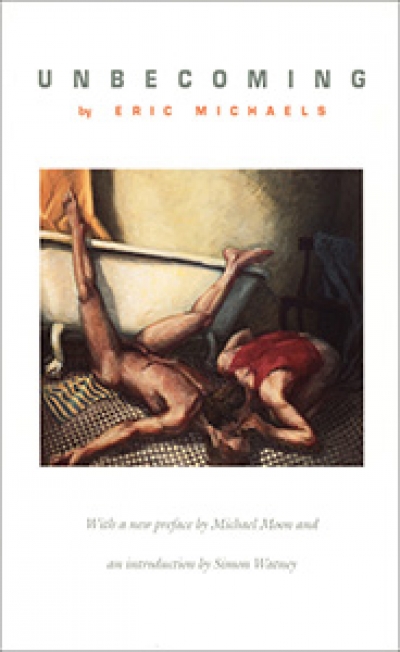

... (read more)I first came across the name of Eric Michaels through a review article he published in the journal Art & Text titled ‘Para-Ethnography’. The article rigorously critiqued Chatwin’s The Songlines and Sally Morgan’s My Place, situating them as ‘para-ethnographic’ texts. It was very impressive. The note at the end remarked that ‘Eric died on 24 August 1988 after a long period of illness’. I heard later on that he had died of AIDS.

... (read more)The Australian Bicentennial Arts Program has been documented in a collection of review articles recently published by Mead and Beckett. It is a record not only of the wide range of arts activities throughout the year but also of some of the issues which confronted the artists involved.

No, it is not an Aborigine on the front of the Australian Bicentennial Authority’s 1988 Reviews (edited by Sarah Overton). It is Mamadou Dioume as Bhima in Brook’s Mahabharata. And don’t be misled by the Aboriginal colours in a contemporary-primitive motif that hovers in the foreground about the title. The essential problem is, evidently, to appear respectable while affirming a vanquished culture (is there a preferable word?) within an imperial medium.

... (read more)The Kurnai of Gippsland: Volume 1 by Phillip Pepper and Tess De Araugo

In 1981 the historian Peter Gardner wrote a moving article in the Victorian Historical Journal on the fate of the Gippsland aboriginal leader Bunjilene, who was thought to be holding a lost white woman supposedly captured by aboriginals in the early 1840s. Bunjilene was first taken into custody by Commissioner Tyers at Eagle Point near Bairnsdale in 1847, but while escaping, his son drowned in the lakes. This was the first in a series of tragedies which was to eliminate the Bunjilene family. When he couldn’t produce the white woman, he was taken as punishment to the Native Police station near Dandenong, even though the authorities knew he could not legally be kept prisoner. Here he was chained to a gumtree for long periods. His wife soon died, and after 18 months of illegal detention Bunjilene himself passed away from ‘grief’. Their two sons were taken away to be educated like whites and displayed around Melbourne. One died early, and the other, after some tragic incidents which revealed his disorientation, succumbed to fever and consumption in 1865. He was only eighteen-years-old.

... (read more)